Between 2013 and 2016 I oversaw the renovation of a 3000-square-foot, five-story 1865 Italianate masonry townhouse in Boston for myself and my family. I originally had purchased the house in the South End Historic District in 1996, well before I received my architecture degree and largely before rampant gentrification and its attendant speculation had swept the neighborhood of much of the social diversity that made it interesting outside of its architectural heritage.

When I first purchased it, the house retained its early Victorian eclectic detailing in many areas, with elaborately-plastered double parlors on the 2nd floor “piano nobile” and an elegant flattened-spiral staircase that ran from the street level to the fourth floor. But the property had been divided and undivided multiple times since its original post-Civil War heyday. The top floor was an alternately frigid or broiling collection of useless little rooms, largely due to the replacement (apparently in 1974) of the southwest wall and part of the roof with a leaking glass lean-to of a sunroom. The basement was an obstacle coarse of steam-pipes and odd slab-level changes, and the street level/ground floor was caught in a transition between a previous owner’s idea of “Ye Old English Kitchen” and somewhere you could actually cook a meal. Meanwhile a hump on the street level floor at the edge of the dining room floor indicated that the something odd had happened to the central line of ancient wood pilings somewhere under the lowest slab. Finally, the two overworked heart surgeons who sold me the property had apparently painted and carpeted much of the townhouse with surplus (and very, very beige) supplies from their hospital, and the wiring as well as much of the plumbing was fastened to joists with rubber tourniquets and medical clamps.

With a bit of construction experience and help from friends and friends-of-friends in the building trades, I painted and plastered and plumbed and had a largely inhabitable house when I moved into it full time as a newly-married husband in in 1997. Sometimes I refer to that work as the “First Renovation,” although it was really more a prolonged case of acting as my own handy-man. By the time I entered architecture school in 2001 (my interest in the field spurred by what I had seen and done with the house), only about two-thirds of the floor area was useful for anything. And soon enough my family was growing.

In 2013, to deal with these various issues and other problems apparent with the townhouse, I had developed a project for a full and thorough second, true renovation.

Essentially, the scheme was

-

- to replace the interior bearing masonry-and-timber wall from the basement slab to the second floor with steel columns supporting wide-flange steel beams;

- to level out the basement slab, once the foundation was upgraded with new helical pilings and grade beams, so that this area would become inhabitable space;

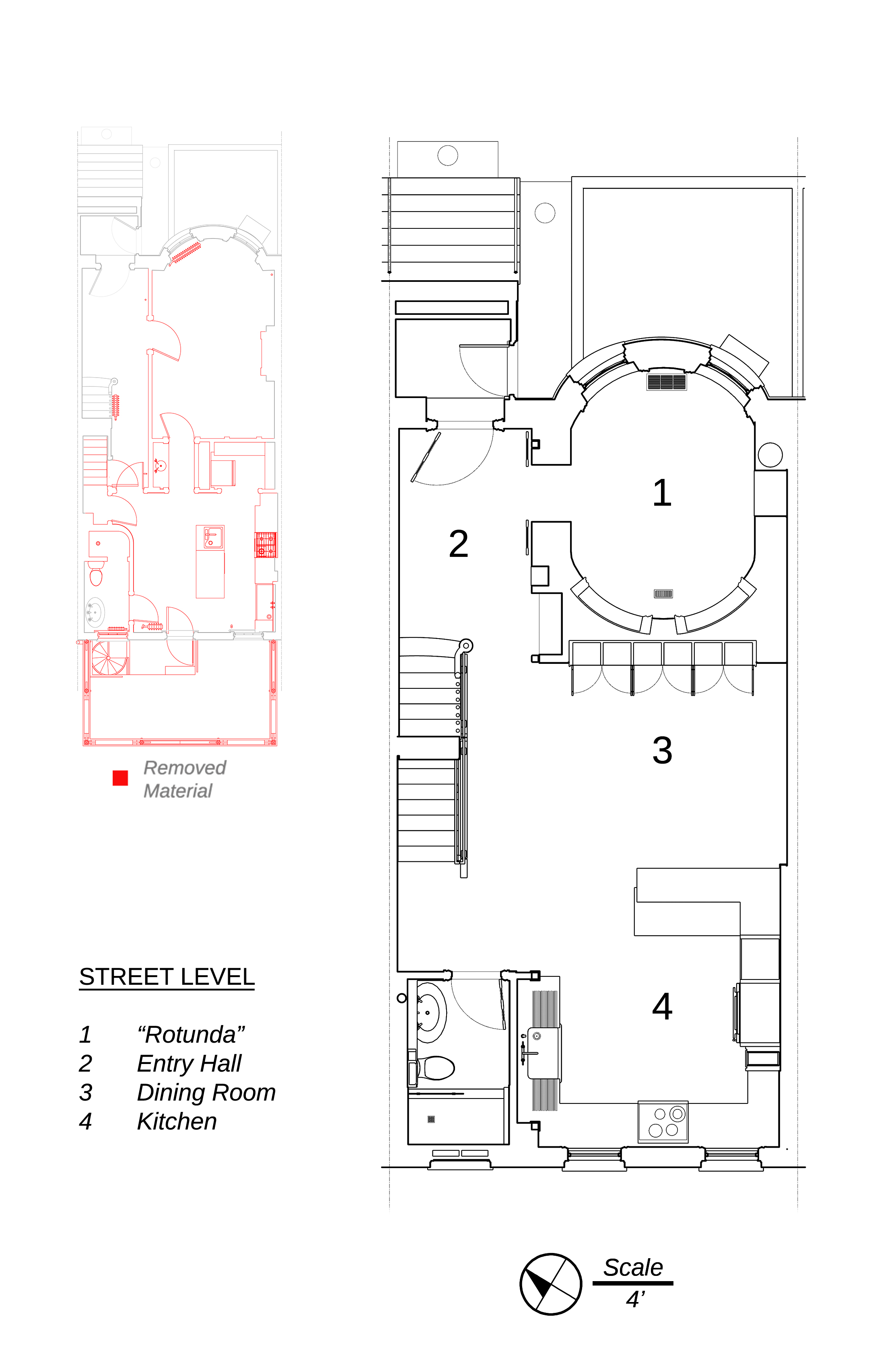

- to completely reorganize the lower two floors, now essentially free of structural elements thanks to the new foundation system and steel framing, thereby creating a new studio, dining area, and kitchen, as well as a convenient utility space and a private study;

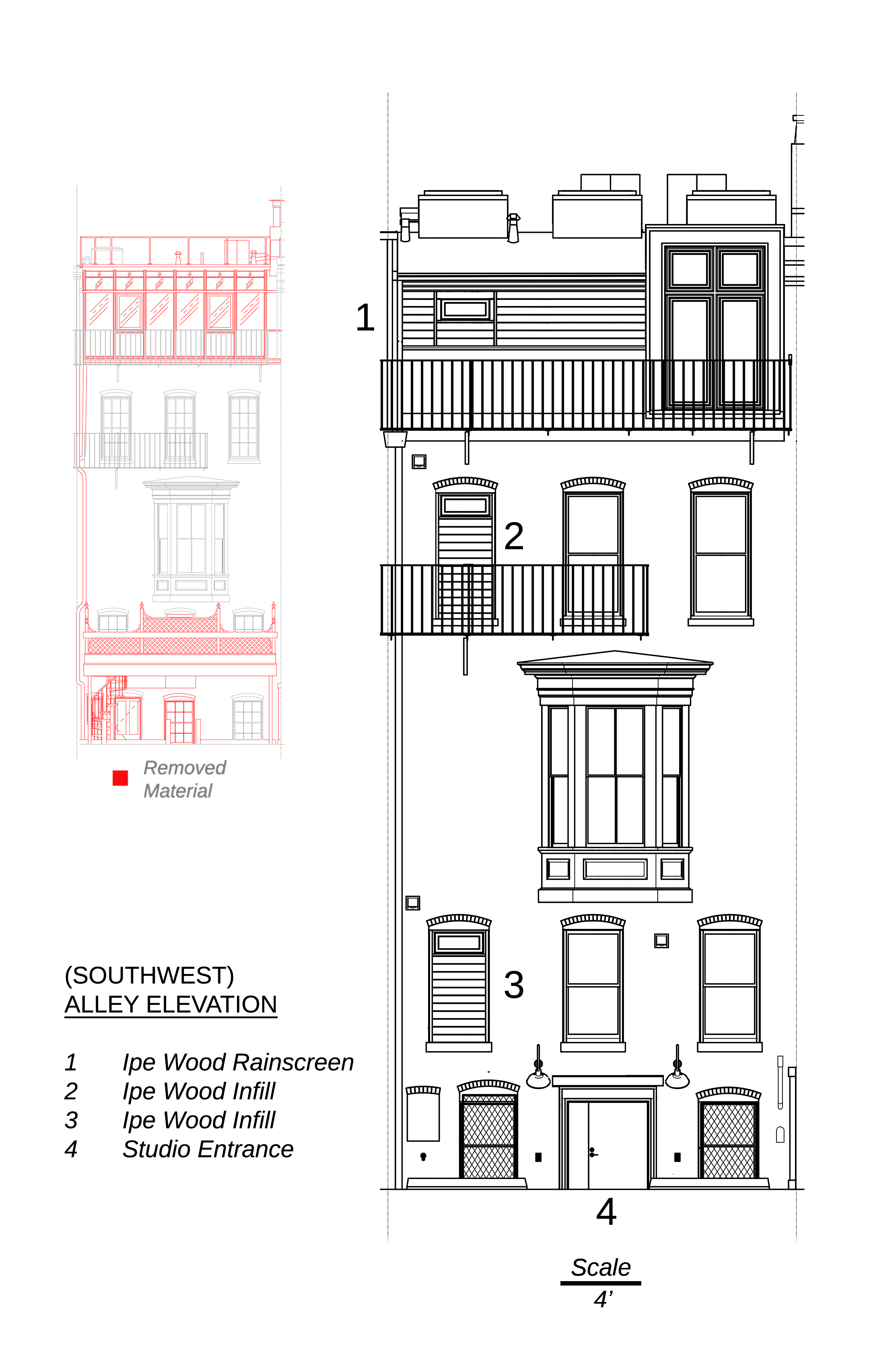

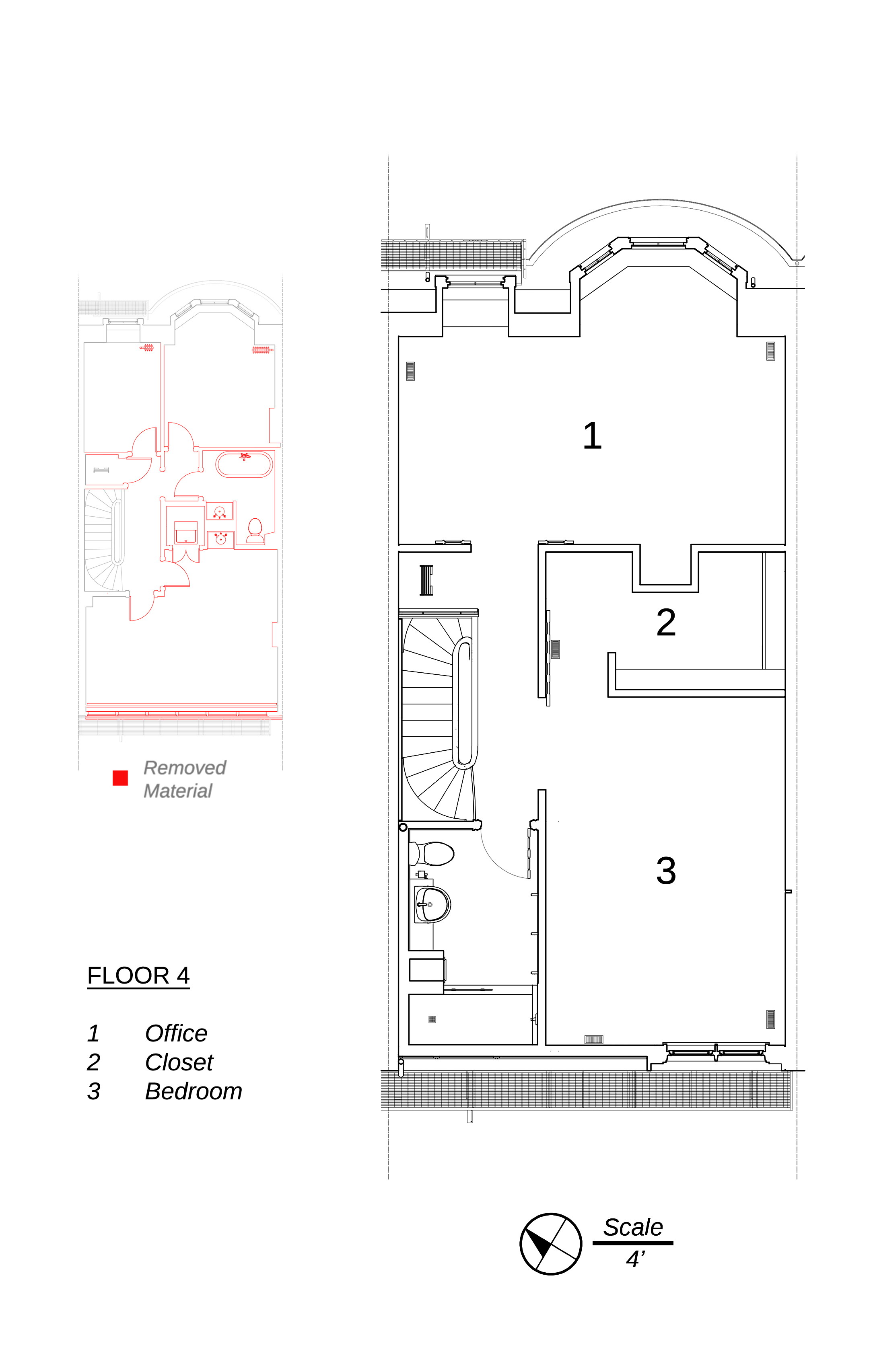

- to replace the inadequate roof joists and the leaking glass lean-to on the fourth floor using engineered lumber joists and modern insulated construction, with the goal of creating a comfortable bedroom suite while preserving the pre-renovation roof “profile” as defined by zoning regulations;

- to replace all windows and doors with code-compliant insulated, modern versions meeting the historic district controls on their appearance;

- to replace all of the services (climate control, lighting, and plumbing) with environmentally-pragmatic modern systems, which of course also entailed insulation and vapor-control strategies as well as three new bathrooms;

- to add an automatic sprinkler fire-suppression system, as “encouraged” by the authorities in the wake of recent disastrous fires in the historic areas of the city;

- and finally to somehow keep the historic parlor level (second floor), with its fragile Victorian-era ornamental plaster ceilings, shored-up and intact while almost all of the building above it and below it was demolished and rebuilt.

As I had expected, given my decade of experience working as an architect on government and institutional renovation projects, that scheme required incessant revision, as demolition revealed new or different issues in the 1865 fabric that was retained. But despite delays, hurried re-designs, and other complications (and no project, in my experience, does not suffer from a few), the work was largely completed and the house ready for inhabitants again by the end of January 2016, while all the odds-and-ends of finish work were put to rest by the beginning of fall that year. This all served as a personal reminder that architecture is an art where one lives for (and in) the end result, and the process of arriving at that end is not necessarily comfortable or worth emphasis in itself.

The structural work and spatial reorganization naturally allowed me to indulge some of my more aesthetic interests. Of course the historic parlor level (the second floor) retained its almost-gaudy nineteenth-century plastered eclecticism, which is what attracted me to the house in the first place back in the late 90’s. Damage done during the sprinkler installation and re-wiring was patched, but no effort was made to cover up over a century’s worth of wear-and-tear otherwise. In fact the reproduction William Morris wallpaper in the rear parlor, removed during the electrical service upgrade, was not replaced, and the old horse-hair plaster surfaces show their patches, cracks, and stains. (This is a nod to artist David Ireland’s famously stripped-down house in San Francisco).

The remodeled street level and the top floor reflect my interest in a sort of universal vernacular (something explored by other architects) and perhaps even a universal exoticism. For instance, on the street level the ends of the curving bookshelves in the “rotunda” project above the flat front of the dining room cabinetry to suggest a sculptural bifurcated mass, like a sort of inverted broken pediment or a closed-off barrow, when the assembly is viewed from the dining room or kitchen. This image is especially obvious (at least to me, the designer) when the lights are off on this floor level, except for those in the rotunda, and the illumination spills across the top of the plastered walls and wood cabinetry into the darkened areas beyond.

The Mexican cement tile used in the kitchen, with its strong pattern apparently derived from the inscriptions of Al-Andalus on another continent and in another time, was selected to reflect my interest in a sort of universal exoticism, a novel ornate tradition with clear origin. The wall of wood strips on the top floor, at one end of the “master” bedroom, reflects a related sentiment.

I’m not the first architect to find himself interested in such things, of course. And there is of course the possibility that what I think I sought to “imply” or “reflect” or otherwise incorporate into the design is in fact only apparent to me. I showed a West Coast architecture critic some of the professional photographs of the finished and furnished townhouse, and he laughed and pronounced the ground floor “nuevo loft” while the parlor level was “a poor man’s John Soane.” (The latter assessment was somewhat startling, since I had looked at Soane’s work for inspiration…but just not for the parlor level.) Those are rather equivocal critiques, in any case. But we must admit the possibility that they do describe the objective reality of my work.

Online Project Albums with Additional Information & Comments:

Principal Project Consultants, Contractors, & Vendors:

-

- Lewis Wadsworth IV, Boston — architectural design, construction documents, construction photos, & additional finished project photos

- Cowen Associates Structural Engineers, Natick — structural consultant

- McPhail Associates, LLC, Cambridge — geotechnical consultant

- Cobblestone Management Inc., Boston — general contracting

- Alpha Masonry & Construction Inc., North Andover — masonry

- Clarion Fire Protection, Inc., West Roxbury — fire sprinkler system

- Rick Disharoon Plumbing & Heating, Walpole — plumbing & furnace

- Dominic Esposito, Boston — masonry

- Frangioso Granite Co., Braintree — interior stone & countertops

- Gilbert & Becker Co. Inc., Dorchester — roofing & copperwork

- Hawkes & Huberdeau Woodworking/Northland Installation Corp., Amesbury — finish carpentry & cabinetry

- Dan J. Hurley, Quincy — HVAC

- Liberty Builders Custom Carpentry Inc., North Reading — finish carpentry & cabinetry

- Longleaf Lumber, Cambridge — reclaimed lumber provider

- Lookout Security Systems, Inc., Watertown — alarm systems

- Model Masonry & Tile, Wellesley — interior tile

- Norfolk Iron Works, Uxbridge — steel fabrication & installation

- Venuti Electrical Services, Inc., Dedham — electrical & lighting

- Wadsworth Painting & Restoration, Duxbury — exterior painting

- Jon Moore — architectural photography (indicated in finished project photo titles)