This post, and these photographs, were revisited and substantially edited in March 2025. Many of the photographs I took during the 2012 visit were made with an early Android tablet, which had as its defining photographic attribute a reliable ability to make panoramic images, either horizontal or vertical. Unfortunately, with the passage of time I’ve come to wish I had used more conventional and higher-resolution digital cameras; in an attempt to rectify the poorer qualities of the panoramas I have used AI-upscaling as well as a modern version of Adobe Lightroom, with limited success.

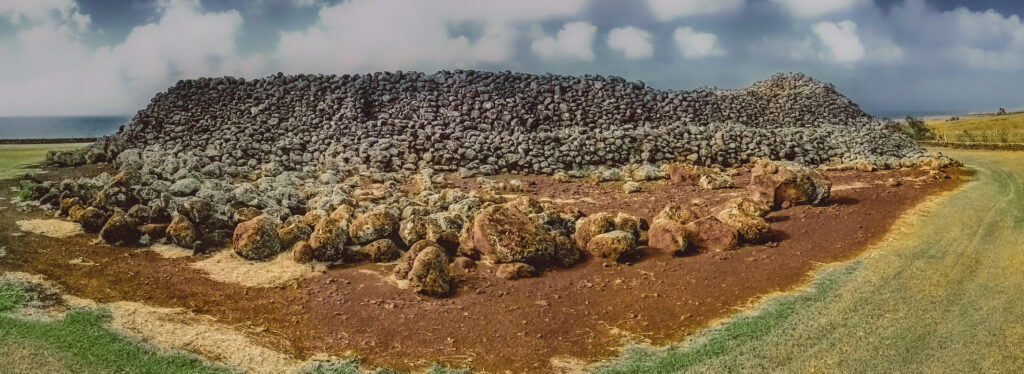

Mo’okini is a heiau, of course, or at least the non-perishable stone remnants of one, which is a Native Hawaiian pre-Contact temple. Specific details concerning it are available from the original application for National Register of Historic Places.

I have an abiding fascination for the rich history and archaeological remnants of pre-Contact culture, not the least because through marriage I am related to people with that ancestry. I am not under any illusions concerning this society: it was a rigidly- caste- divided, warrior- dominated, feudally- organized police state with strong theocratic elements and a notable lack of regard for the supposed sanctity of human life, possibly as a result of the recurrent Malthusian pressures on a human population isolated on a resource-poor archipelago. Mo’okini was a luakini heiau, reserved for the use of Aliʻi Nui royalty (it was originally the temple of the family of the epic unifier of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Kamehameha the Great, and the location of his hereditary idol of the war god, Ku-ka-‘ili-moku). It may have even been the first heiau of the final iteration of the strict Polynesian religion of Hawai’i, built on the site where the murderously- reactionary- and- probably- not- legendary Samoan priest Paʻao established a temple in an effort to “purify” Hawaiian culture. It was also a place of regular, horrific human sacrifice, where bodies of the conquered (or anyone else whose existence was inconvenient to the dominant Aliʻi) were broken down and served to the war god. Technically, the execution and butchering occurred outside of the temple enclosure, on or using a large monolith called a holehole; several candidates for this artifact are still existent at the site. Only the prepared portions of the hapless victims were brought inside the walls for the hungry deity.

The pre-Contact Kānaka Maoli did not shape stone when they could avoid it, but instead placed an odd tectonic value on the characteristics of each piece as it was found. The water-rounded stones composing the heiau (precious on an island of jagged basalt without major rivers), for instance, were passed hand-by-hand by thousands of men from a location over ten miles away.

But the most interesting aspect of Mo’okini for me, as architect, is a bit less explicable. On my visit in 2012 to the lonely site, I found it strangely difficult to comprehend the dimensions of “the building”; it seemed bigger on the inside than it could possibly have been. I’ve examined satellite photographs; the rectangular enclosing walls only measure 260’ by 125’ feet at best. But inside those high walls (three times the height of a grown man!), the space seems measurelessly huge and difficult to define as rectangular or any sensible shape. The uncanniness of the experience still troubles me; for all their flaws, these tablet-made panoramas from 2012 do seem to capture the unaccountable vastness of the interior.

Interestingly enough, I’ve tried to go back to verify my impression, and it’s never worked out. My return with better equipment has been invariably thwarted by peculiarly bad weather and a road that is so impassible that its condition must be deliberate on someone’s part.

Leave a Reply