This is a very small project, driven by expediency, and at first I hesitated to list it among my projects. But I did learn an important lesson (see below). So here goes:

I had originally purchased this 950-square-foot, single-bedroom 1892 townhouse—two narrow floors, a roof deck, and a semi-finished basement, all connected by a spiral oak staircase—in the South End Historic District on a forgotten colonial sidestreet as an investment. It was at the time one of the smallest single-family houses in the whole city, less than twelve feet wide between the party walls and only slightly larger in floor area than the famous Spite House in the North End. In 2012 I decided to use it for my own family home while I renovated my other property—see Palazzo (2013-2016).

This little house is in theory regulated by city ordinances to prevent any obvious alteration to its late Victorian exterior facades, down to the profile of the window muntins. The other important original constraint, outside of the usual building codes and the historic district exterior limits, was the notion that every element of the proposed work should be “as of right” with regard to the various zoning and building regulations, meaning essentially no change was permitted to the building footprint or gross floor area. Any proposed change to the building that was not “as of right” would require public, notoriously-delayed hearings with notoriously-unsympathetic officials, and would allow abutters or nearby property owners (or, just as often, any local panjandrum with a dislike of the noise of nearby construction, or just a grudge) to object to or request modification of any non-conforming element of the proposed project—or worse, delay all work through “death by appeal”. Only the very rich or the very connected (or those who were both, the local oligarchs) could afford to ignore the “as of right” conundrum; mere mortals who wanted their projects completed in a reasonable timeframe on budget towed the line.

Those restrictions as well as the already-tight budget and limited available construction period (eight months) resulted in that most invisible of complex projects, where much looks the same as it did before the work began but hopefully meets the users’ needs more reliably. The budget was further constrained after un-repaired hidden damage from an early twentieth-century fire was discovered to have compromised floor framing, requiring unexpected structural remediation.

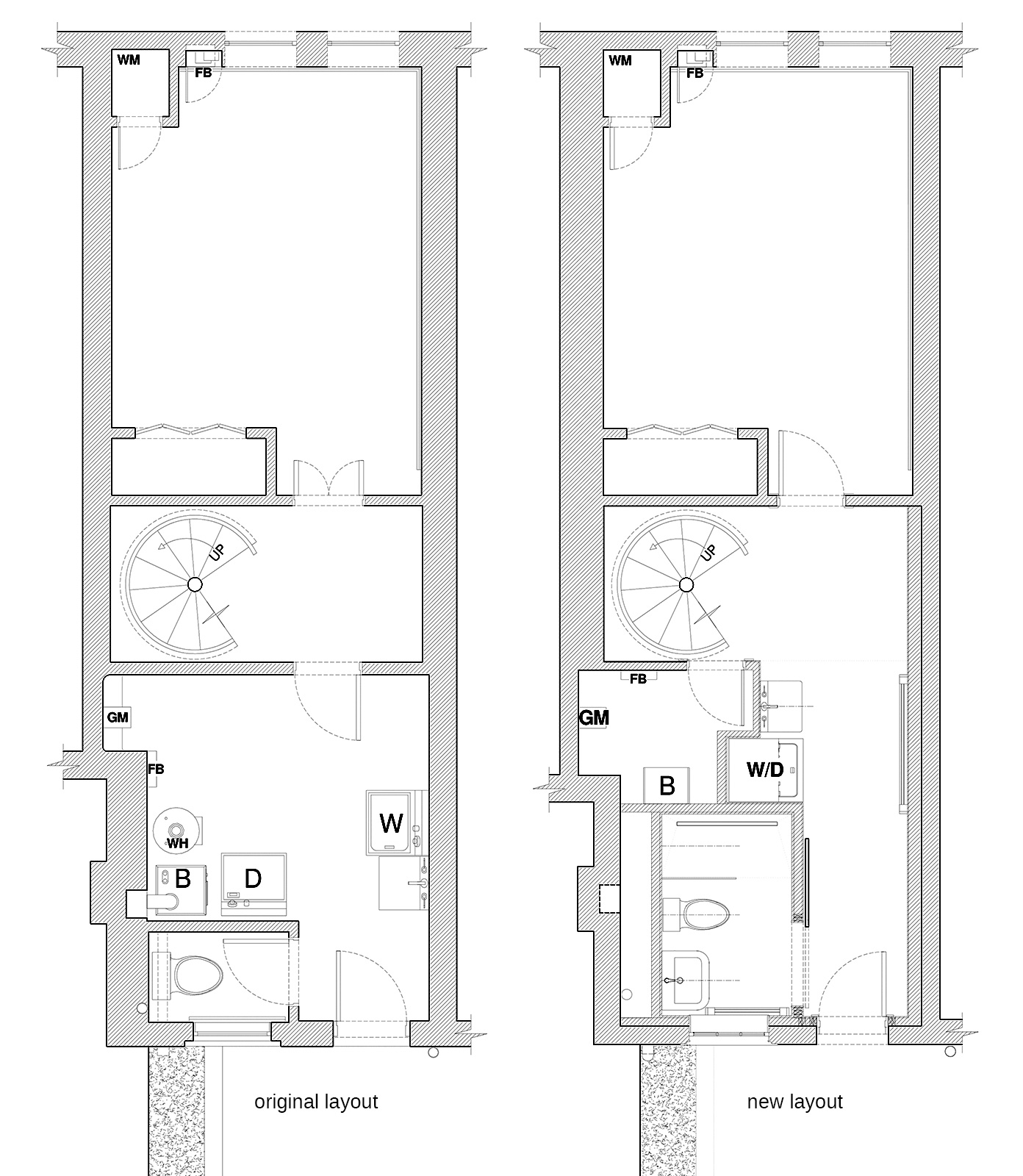

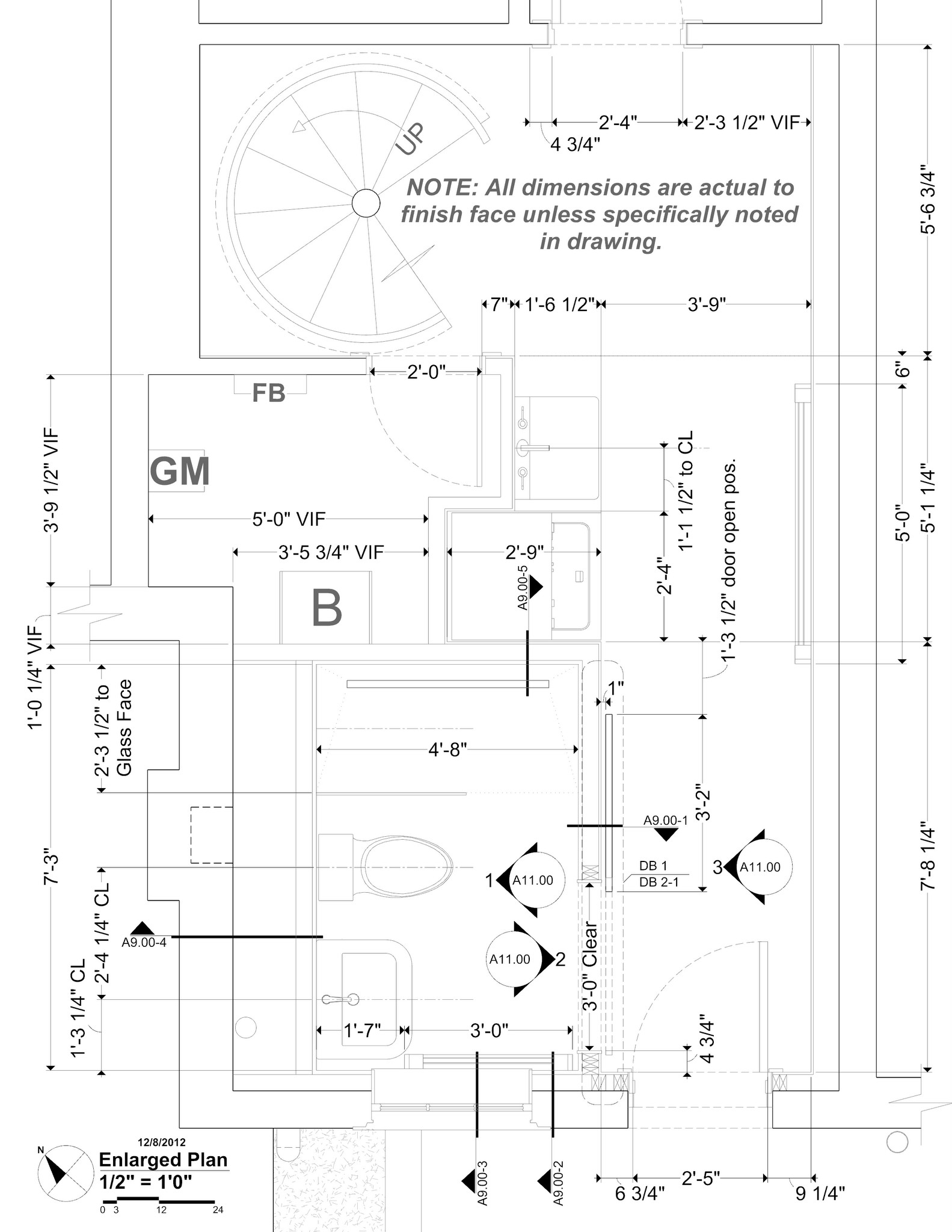

The project here included the approved replacement of those historic windows; the upgrading of the heating, plumbing, and electrical systems; and the installation of air conditioning. The most visible changes from the pre-Lewis period lay in the spatial reorganization of the basement level, which prior to the work consisted of a single front room, a very large utility room, and a small closet-like space with a toilet. By altering the interior partitioning as well as by replacing the furnace and hot water tank with a small high-efficiency, on-demand water-heater/boiler, I was able to free up enough space in the basement for a tiled bathroom with a vanity and a door-less shower that fit (both in terms of comfort and building codes) within a 7’3″ by 4’8″ area, thus making the room at the front of this level actually useful as additional bedroom space, if a somewhat nebulously-permitted one given the low ceiling height. The improved layout is best understood by comparing the original floor plan for the basement level to the realized design.

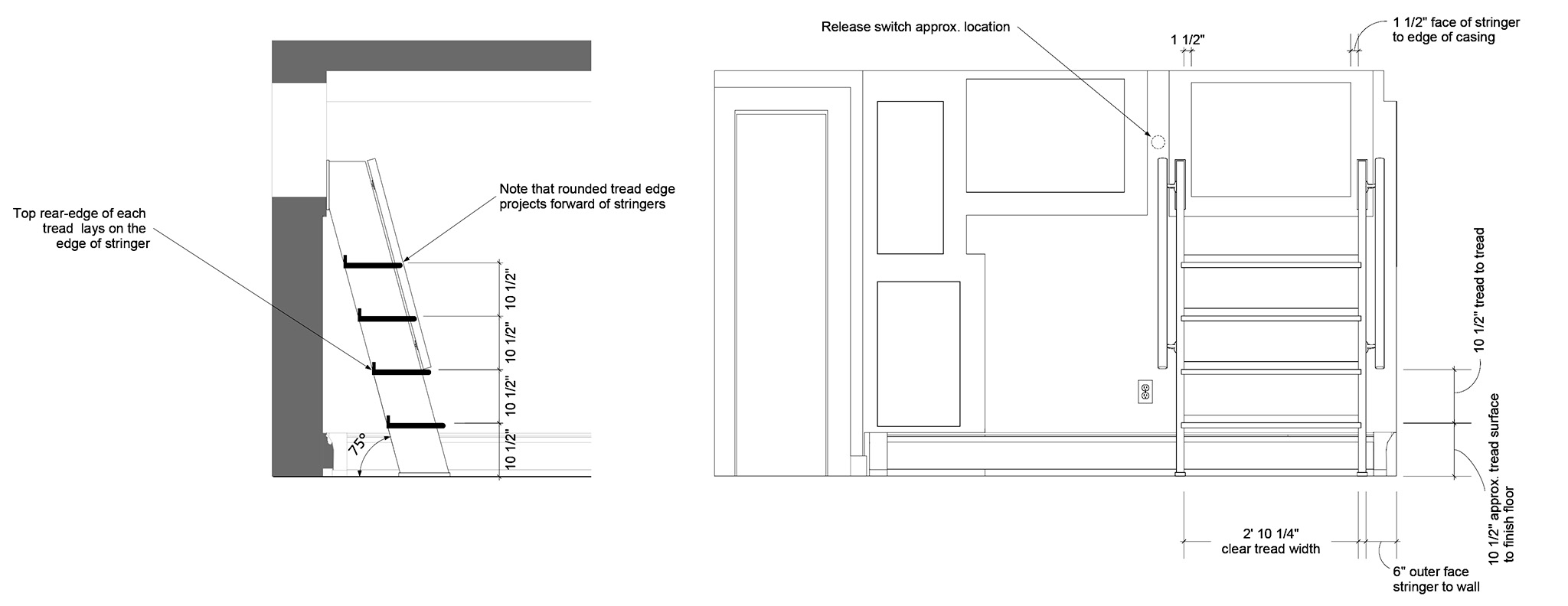

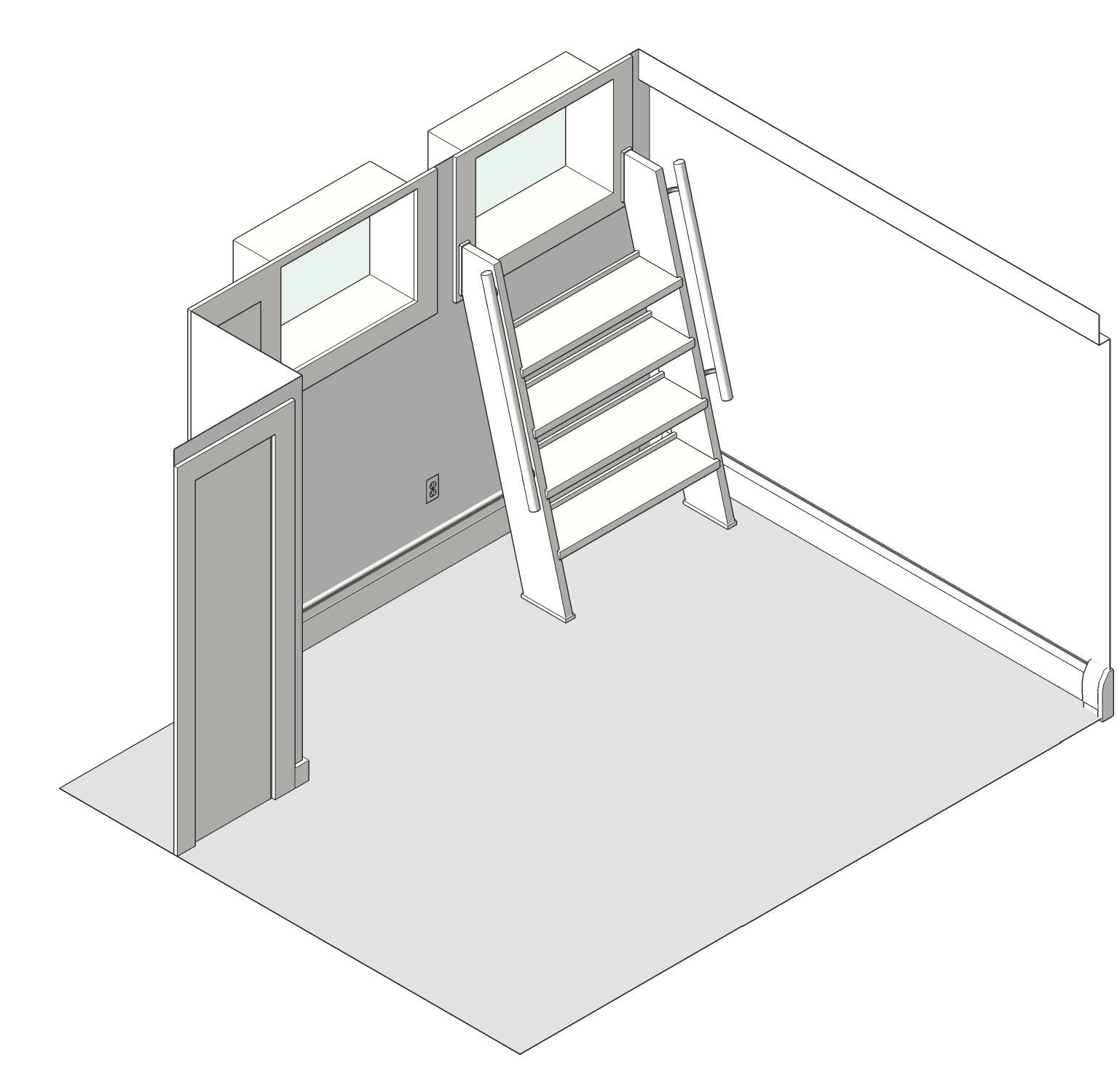

There was also an interesting emergency egress issue that concerned me with that front basement room: the two windows onto the street were relatively high up from the floor, 55” to the sill. I designed a kind of sturdy built-in bookcase that could function as a staircase in a crisis and replaced the lock on the exterior security grate for the window above it with a electromagnetic latch that would open automatically on loss of electric power or if the large “panic” button inside next to the window was pressed.

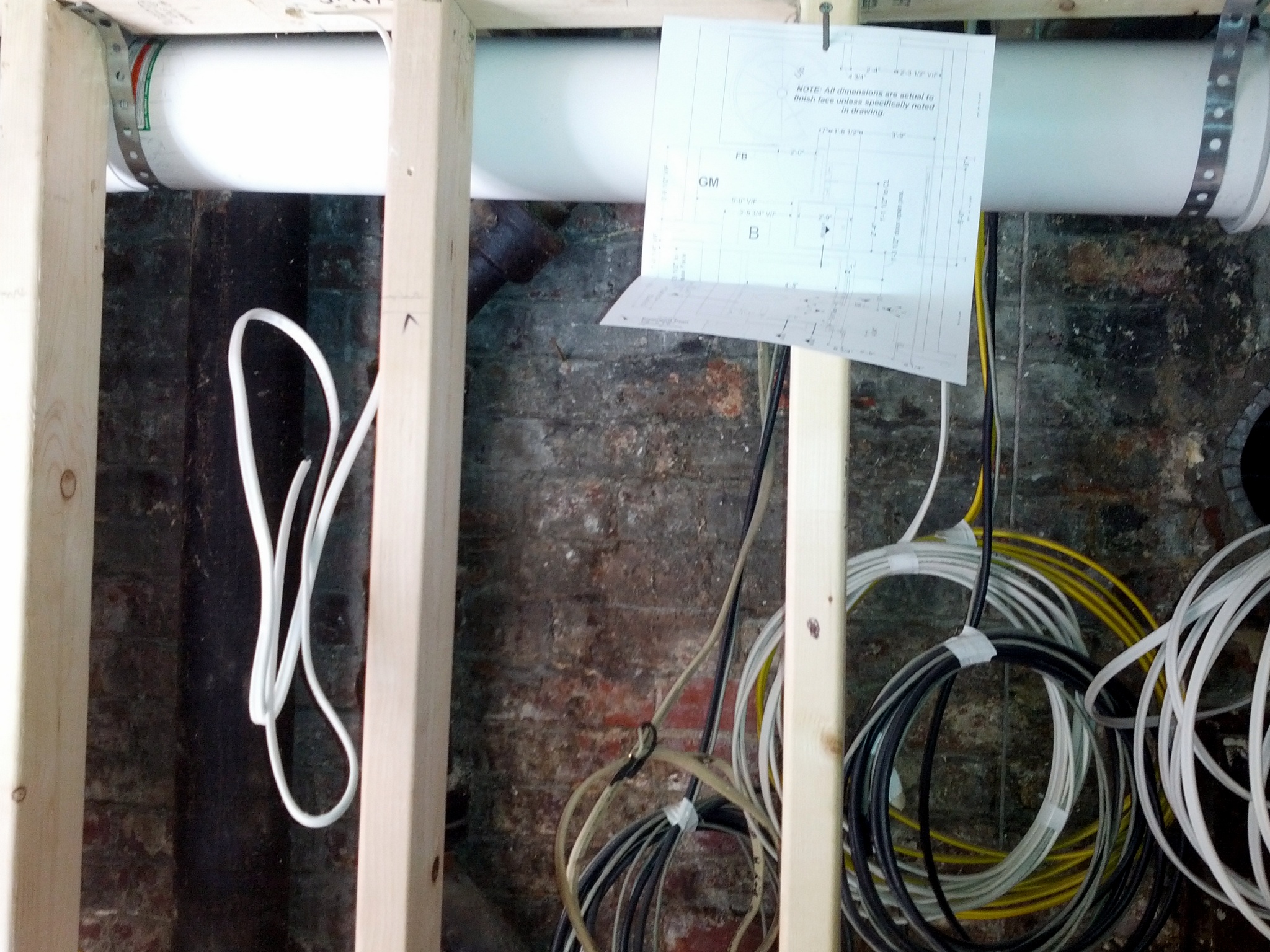

That “minimal bathroom” design for the other end of the basement required countless layout and finish studies, shared with the tradesmen in an effort to get the best results in the time and budget available. The builders ultimately asked for site copies of renderings of the approved designs, claiming that these were nearly as valuable to them as the actual construction drawings. I would find copies stapled to the framing or among the tools when I performed my construction administration visits.

For the most part, my intervention was successful and we all lived comfortably—“cozily” even—in our little palazzetto on a forgotten street. In early 2016 my other construction program at my other property—il mio palazzo—was completed, and after some debate we decided that I should place the little house on the market in order to recoup some of the expenses the two projects had entailed.

And this is the point where I extracted my last but perhaps most important experiential lesson as an architect from this little project: in three days—the current national housing crisis had settled firmly upon the city since I had purchased the building—the little house sold for nearly twice my asking price in a bidding war between multiple interested parties from as far away as California. Great for me, right? Well, perhaps from a financial point of view.

The winners of this bidding war with a cash offer were the young scions of a major real estate developer, both very wealthy and very connected, as described above. In short order, they stymied those notoriously unsympathetic city officials and seemingly bulldozed the neighborhood panjandrums…and in no time they gutted the little house down to the four exterior walls. They dug out the basement; no low ceilings for them. They put in bigger windows and changed the historic facades. And they added a whole half-floor to the top of the house for “a master suite”. So this is no longer the second-or-so-smallest single family house in the city. I’ve not been inside since I sold the property, but the outside has some very impressive modernist flourishes visible from the street, lovely but in defiance of the spirit at least of the historic district codes. This is not to imply that the people who purchase the little house were terrible in any way; if I had access to the same resources, I might have done much the same when I was renovating the building three years earlier.

But here’s the lesson: Money and power are the most important requirements for a successful architectural project; everything else—good taste, a clever design, a decent imagination, practical project management—is ultimately irrelevant.

Architecture itself is ultimately irrelevant in the pursuit of a construction project, of a work putatively of architecture. Only the money and the power to grind down all opposition qualitatively matter.

That is not a lesson imparted in any architecture education program or history book of which I am aware.

General Contractor for this renovation: Quality Services Inc., Boston, Massachusetts

Leave a Reply