Mysteriously, when I was an architecture student and everyone hated me, I found solace in the works of Nicholas Hawksmoor (d.1736).

Actually, that sounds silly and made-up but it is probably-most-likely-largely true. Also, really-actually-mysteriously I had somehow acquired a copy of Hawksmoor’s London Churches: Architecture & Theology by Pierre de la Ruffinière du Prey (2000), published just shortly before I began architecture school. Where did it come from? I remember seeing it on my drawing table in the A&A; I remember one of my fellow YSOA students picking it up, paging through it, making an exaggerated “gagging face”, and putting it back down.

Classical (Graeco-Roman, all’antica, or however you want to refer to it) architecture was not particularly popular at Yale, even though postmodernist architect-survivor Robert A.M. Stern was the dean at the time. We were also not quite at “peak Hawksmoor” — the rehabilitation and even ascendency of the old master’s reputation — which I would say coincided with the final restoration of the interior of Christ Church Spitalfields in 2004. In 2001, Hawksmoor was still often regarded as a footnote in architectural history, a plodding commoner assistant to the baroque lords Christopher Wren and John Van Brugh. I am not sure then, or even now, what beguiles me so in Hawksmoor’s work, even though post-War architectural historian John Summerson had as early as 1945 waxed enthusiastic over the famous churches with their odd exaggerated details and described them as “suggesting the extravagance of dream-architecture.”

I’m all about dream-architecture, or more likely nightmare-architecture, and always have been. I’m not kidding when I announce that my career goal is to design haunted houses.

Incidentally, I don’t believe that I had consciously visited any Hawksmoor churches, or any other of his works, during my travels in the UK by that point, although I have done so now. I actually wasn’t interested in designing classical architecture, either, during architecture school except to offend the doctrinairely modern — if I was going to be treated like an outcast, at the very least I was going to make certain I deserved it.

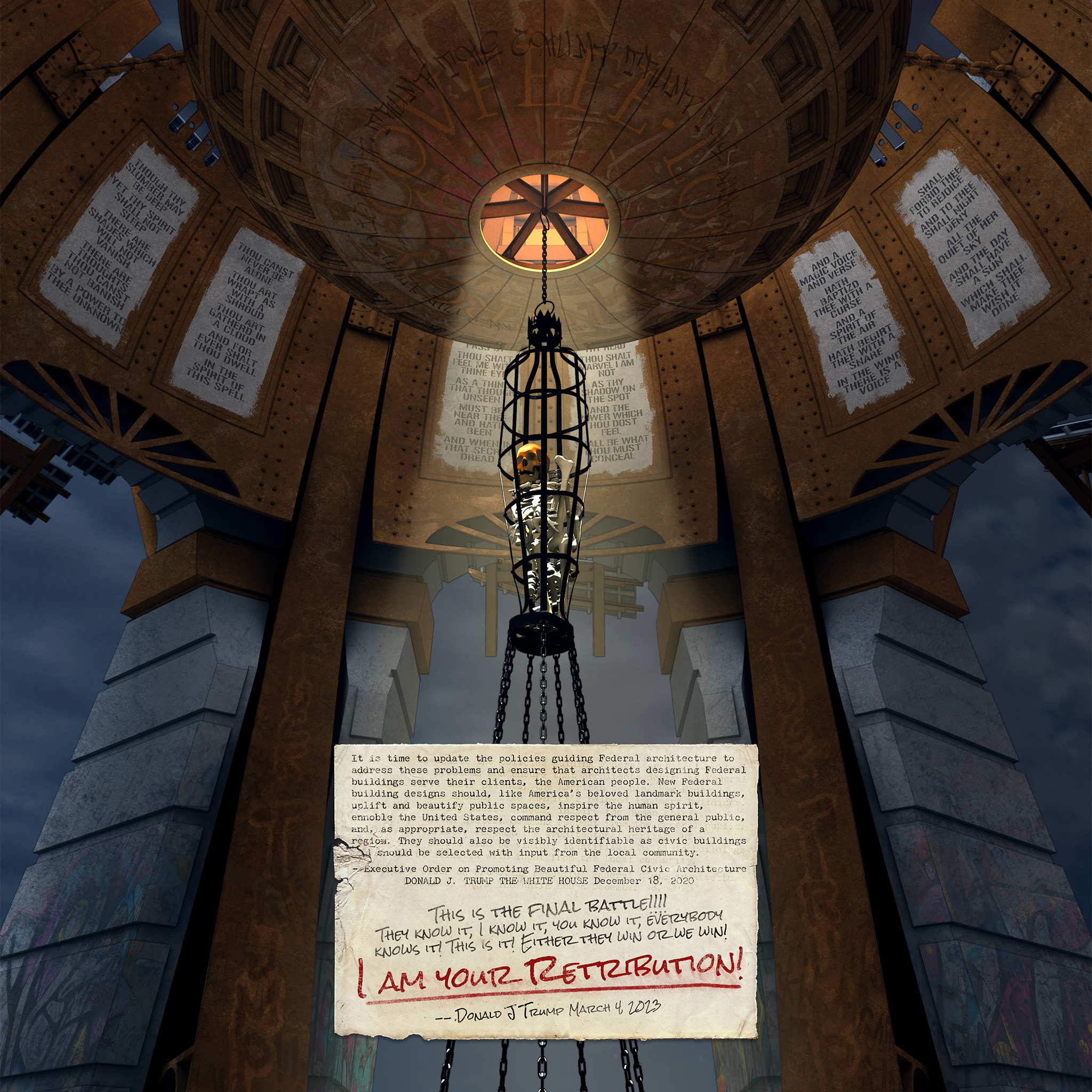

…T.S. Eliot The Waste Land, Ian Sinclair Lud Heat…but then (and I almost launched into a paraphrase of David Bowie’s “Judy” speech in the David Lynch film Fire Walk With Me) let me tell you about Hawksmoor — not our baroque architect but the 1985 postmodern horror/detective novel of that name by author Peter Ackroyd. This last proved to be particularly intriguing to would-be-architect of haunted houses me. The principal charm of the work is the lively faux-Pepys narrative of Nicholas Dyer, the novel’s alternative version of the baroque architect. Rather unlike the original, who was admired by clients and rivals alike for his genial, “agreeable” nature, Dyer is a persecuted genius, brilliant, glib, resentful…and also a murderous occultist, surreptitiously creating through his architectural craft, careful surveying, and the odd human sacrifice a mystical means of escaping this “dung heap” mortal world of ours for eternity. The eponymous Hawksmoor, in Ackroyd, is a modern police detective investigating a series of high-profile murders in bleak 1980’s London around Dyer’s historic churches, potentially carried out by a tramp who might be called “The Architect” — you can guess who that really is.

The novel famously launches with Dyer giving his hapless ‘prentice Walter his devoirs:

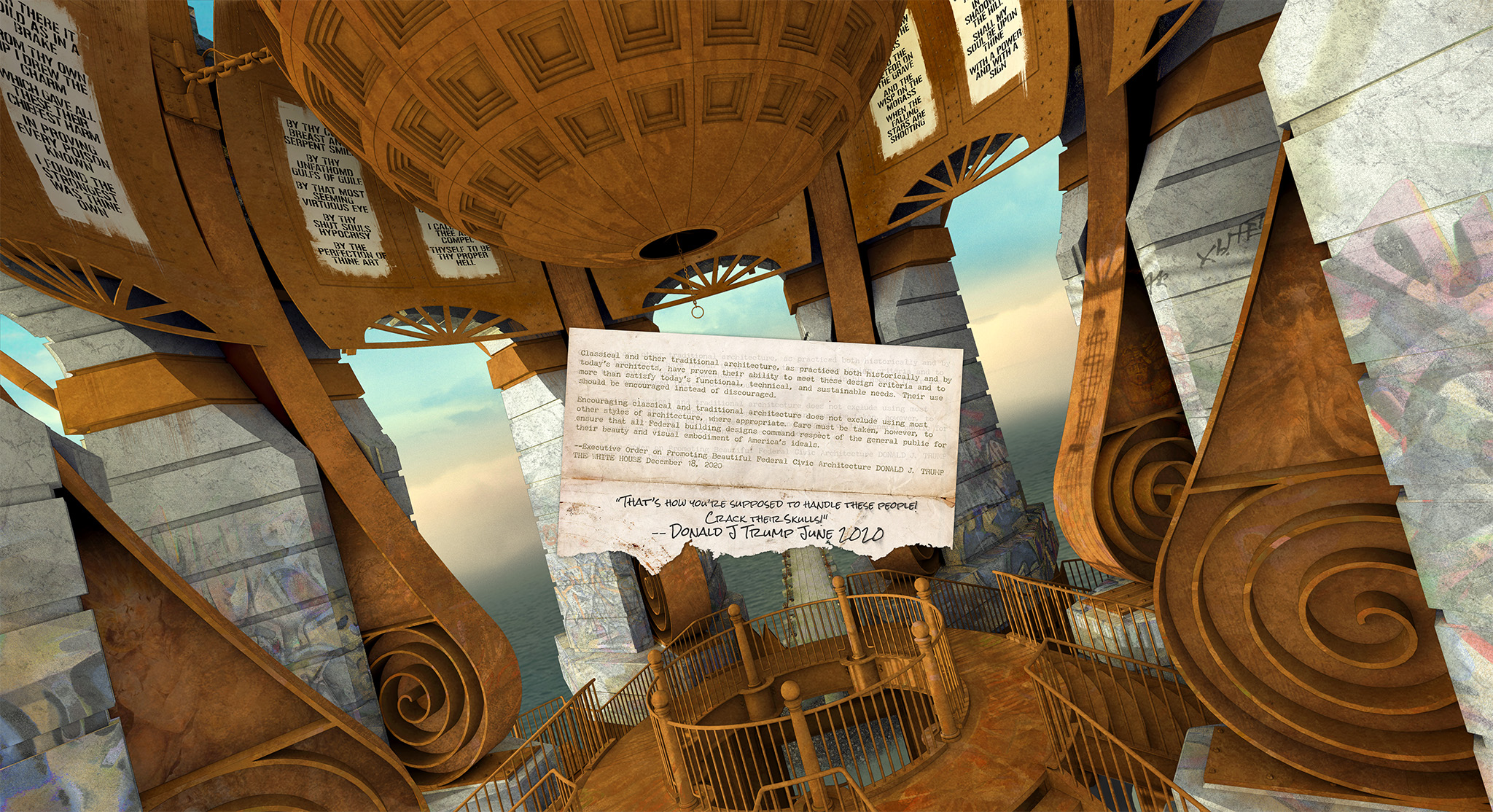

AND SO let us beginne; and, as the Fabrick takes its Shape in front of you, alwaies keep the Structure intirely in Mind as you inscribe it. First, you must measure out or cast the Area in as exact a Manner as can be, and then you must draw the Plot and make the Scale. I have imparted to you the Principles of Terrour and Magnificence, for these you must represent in the due placing of Parts and Ornaments as well as in the Proportion of the several Orders: you see, Walter, how I take my Pen? […]

[…]And now we come to the Heart of our Désigne: the art of Shaddowes you must know well, Walter, and you must be instructed how to Cast them with due Care. It is only the Darknesse that can give trew Form to our Work and trew Perspective to our Fabrick, for there is no Light without Darknesse and no Substance without Shaddowe (and I turn this Thought over in my Mind: what Life is there which is not a Portmanteau of Shaddowes and Chimeras?). I build in the Day to bring News of the Night and of Sorrowe, I continued, and then I broke off for Walter’s sake: No more of this now, I said, it is by the by. But you’ll oblige me, Walter, to draw the Front pritty exact, this being for the Engraver to work from. And work trewe to my Design: that which is to last one thousand years is not to be praecipitated.

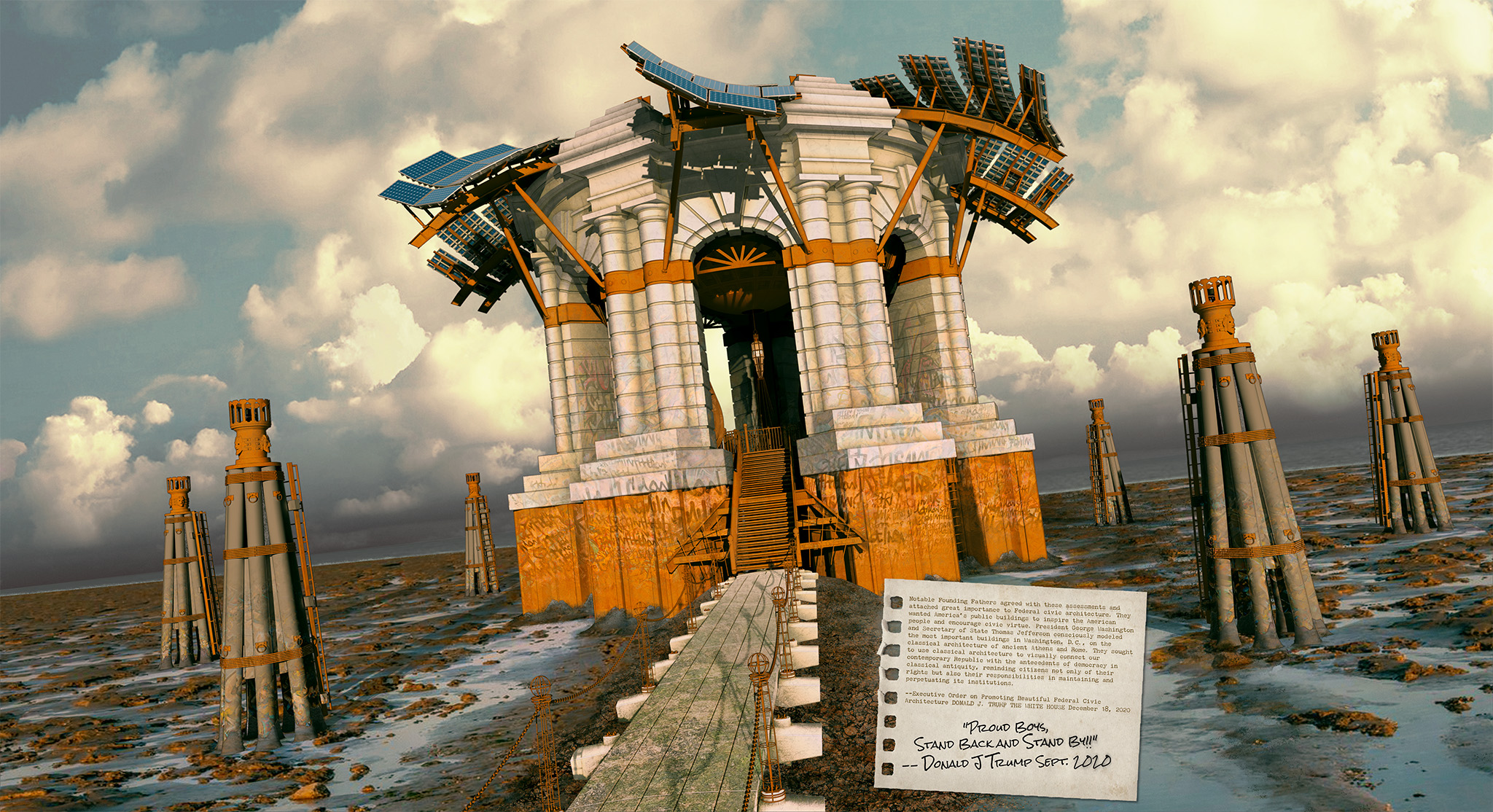

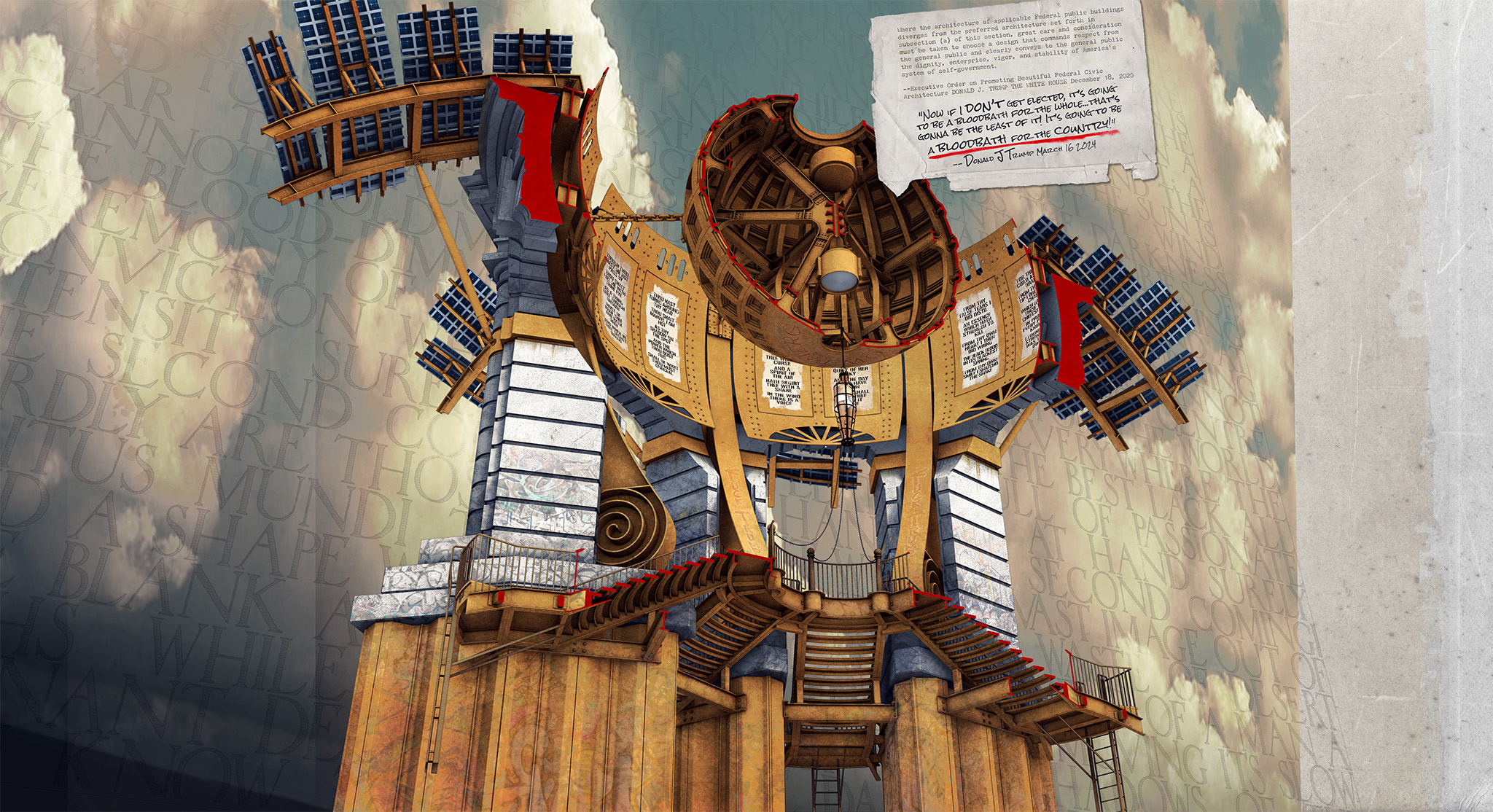

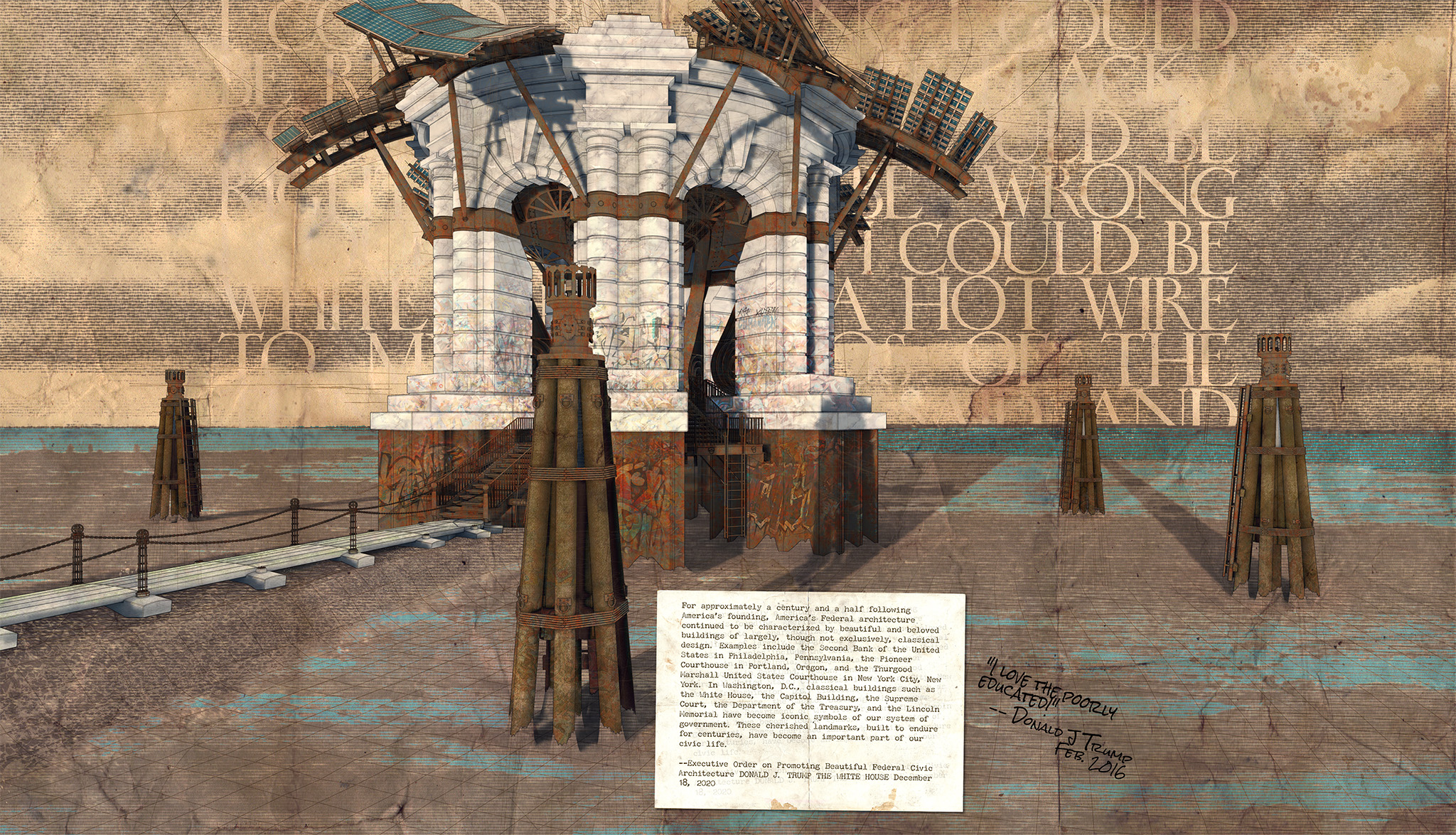

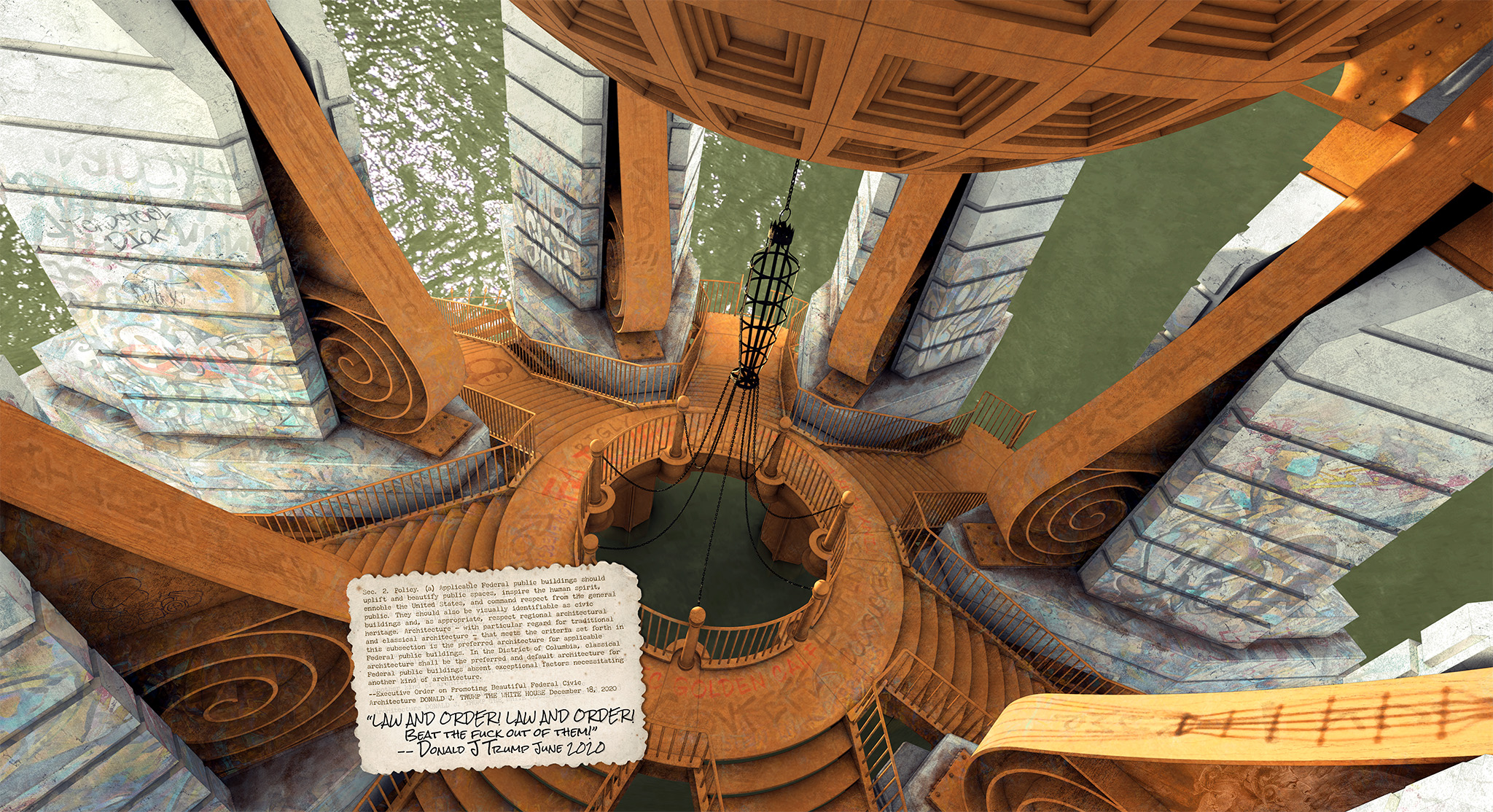

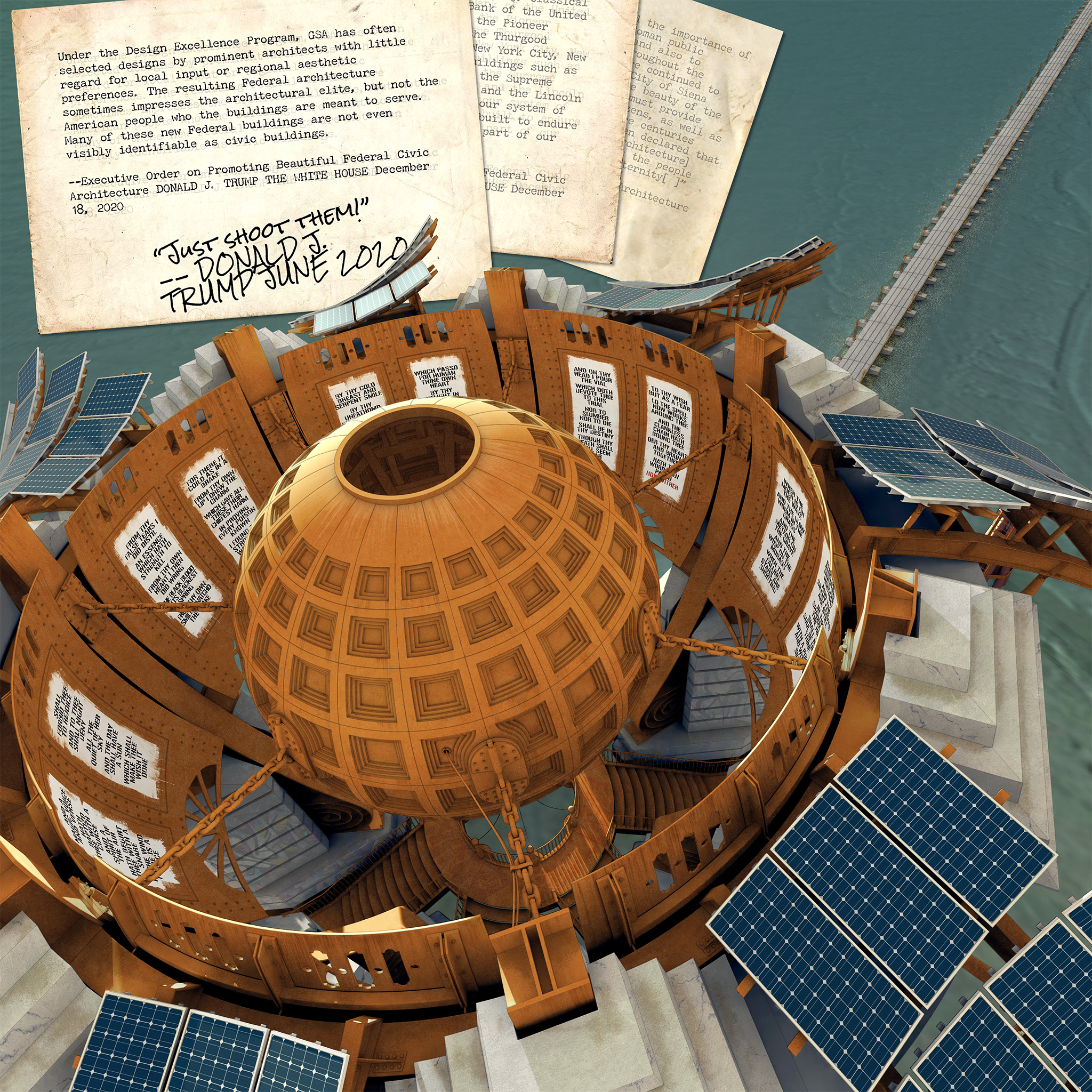

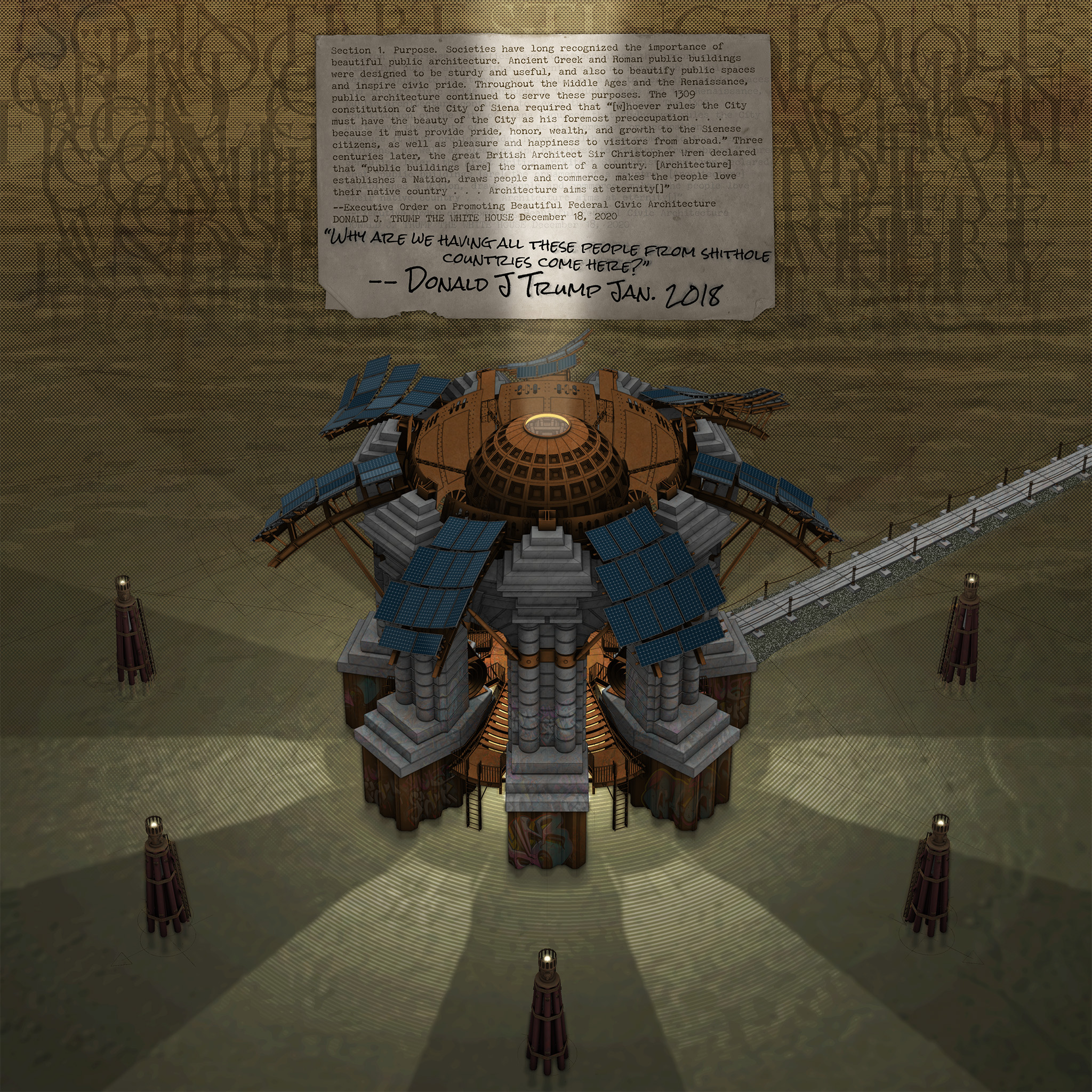

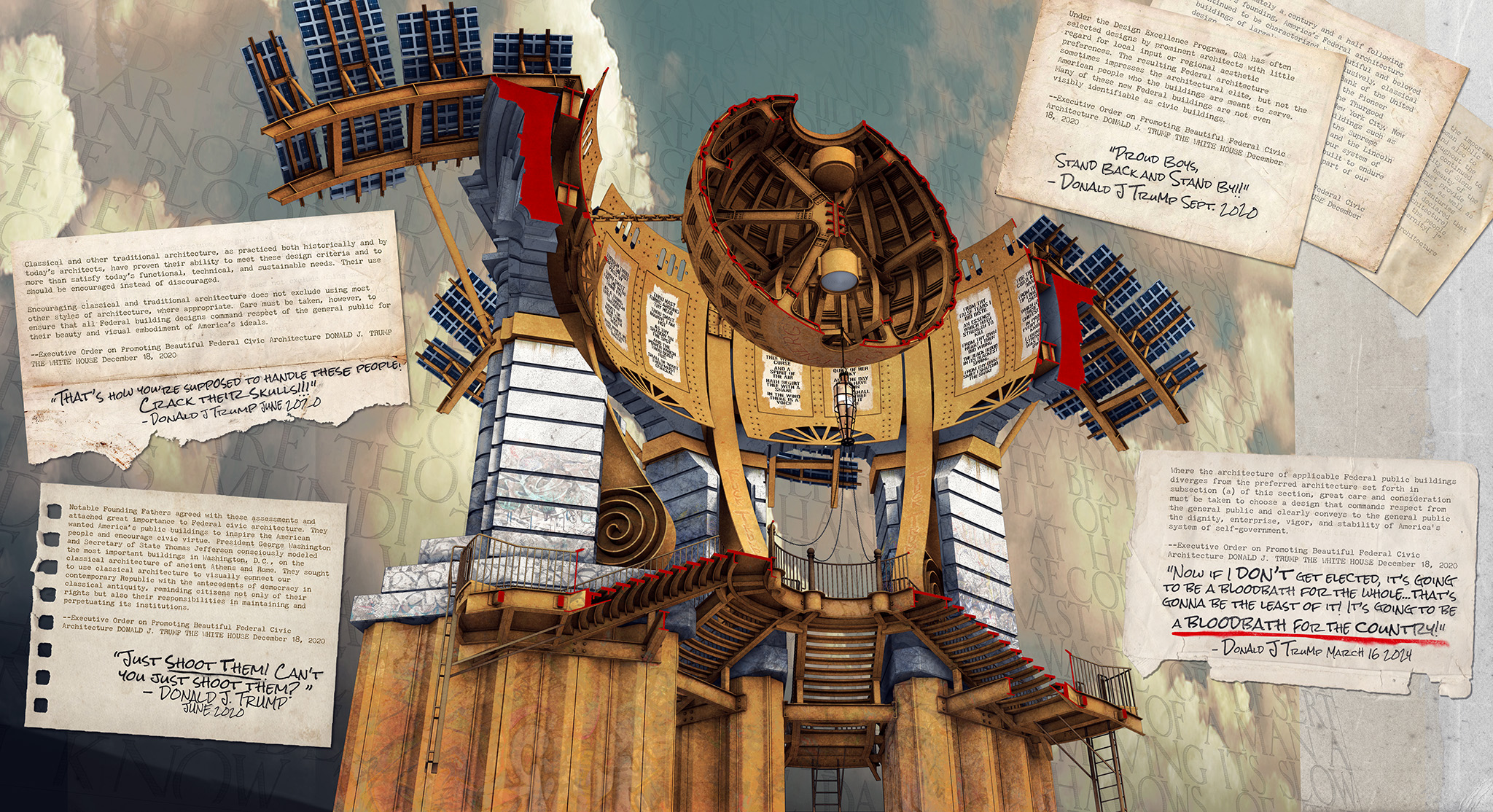

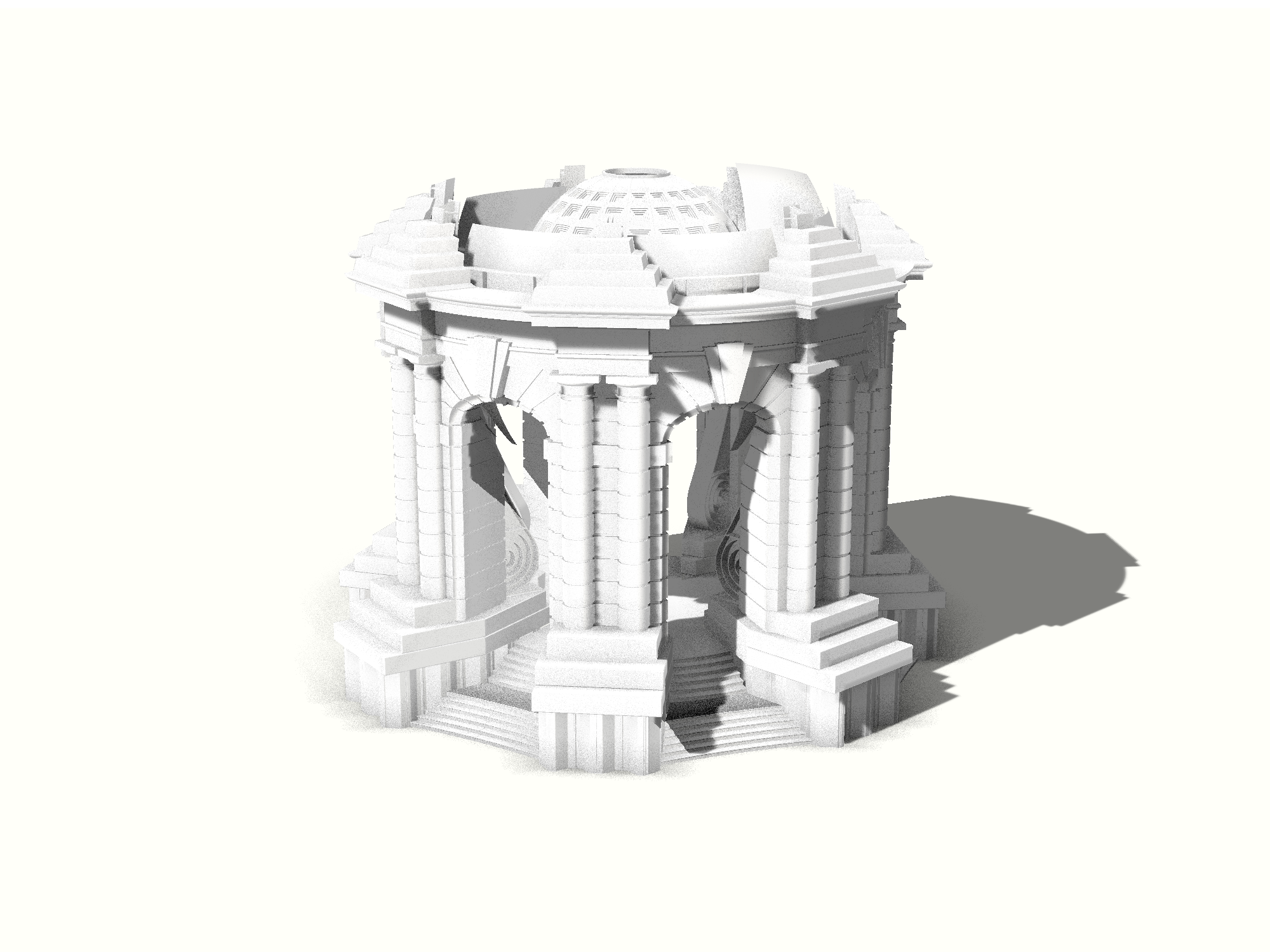

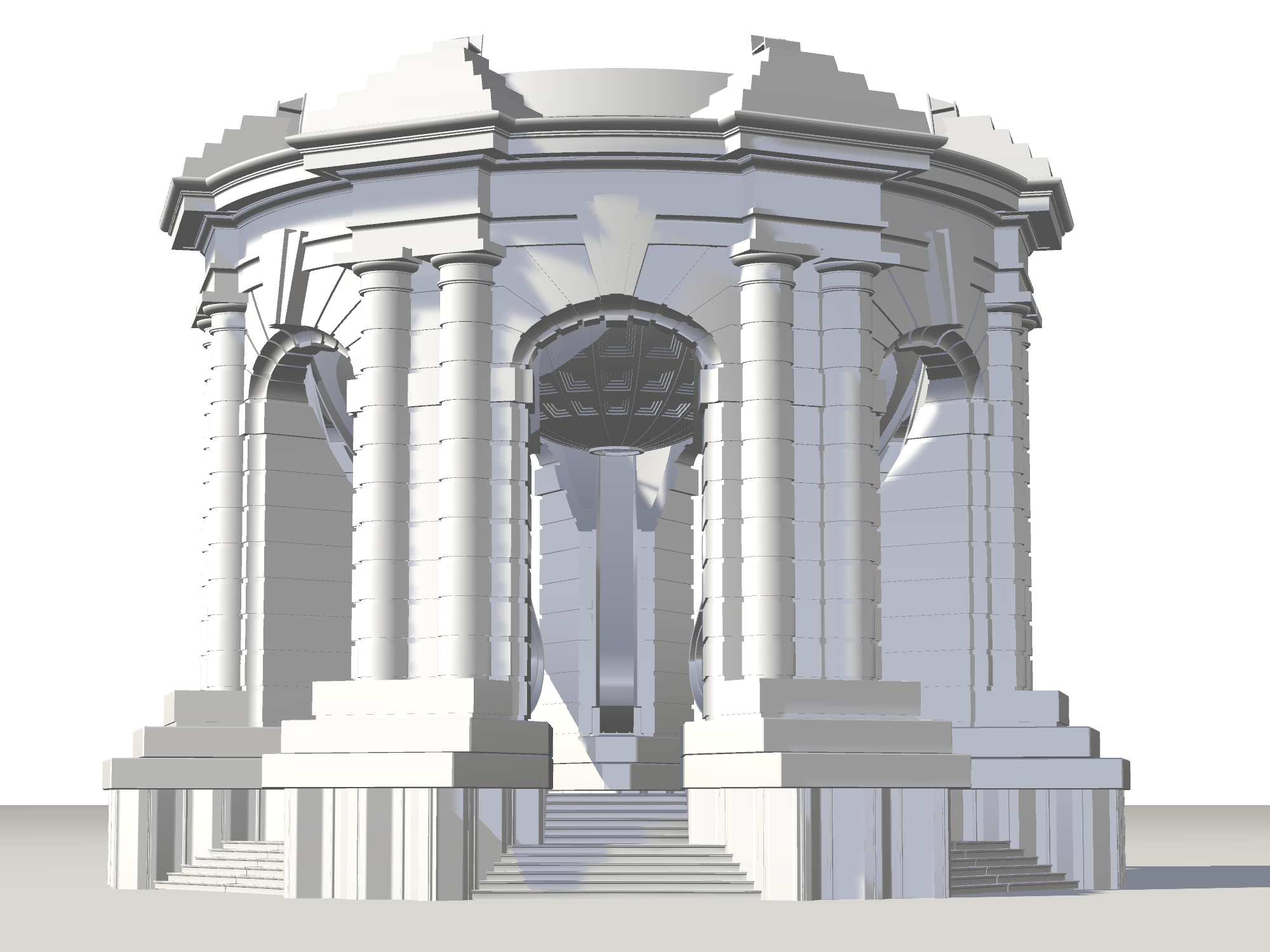

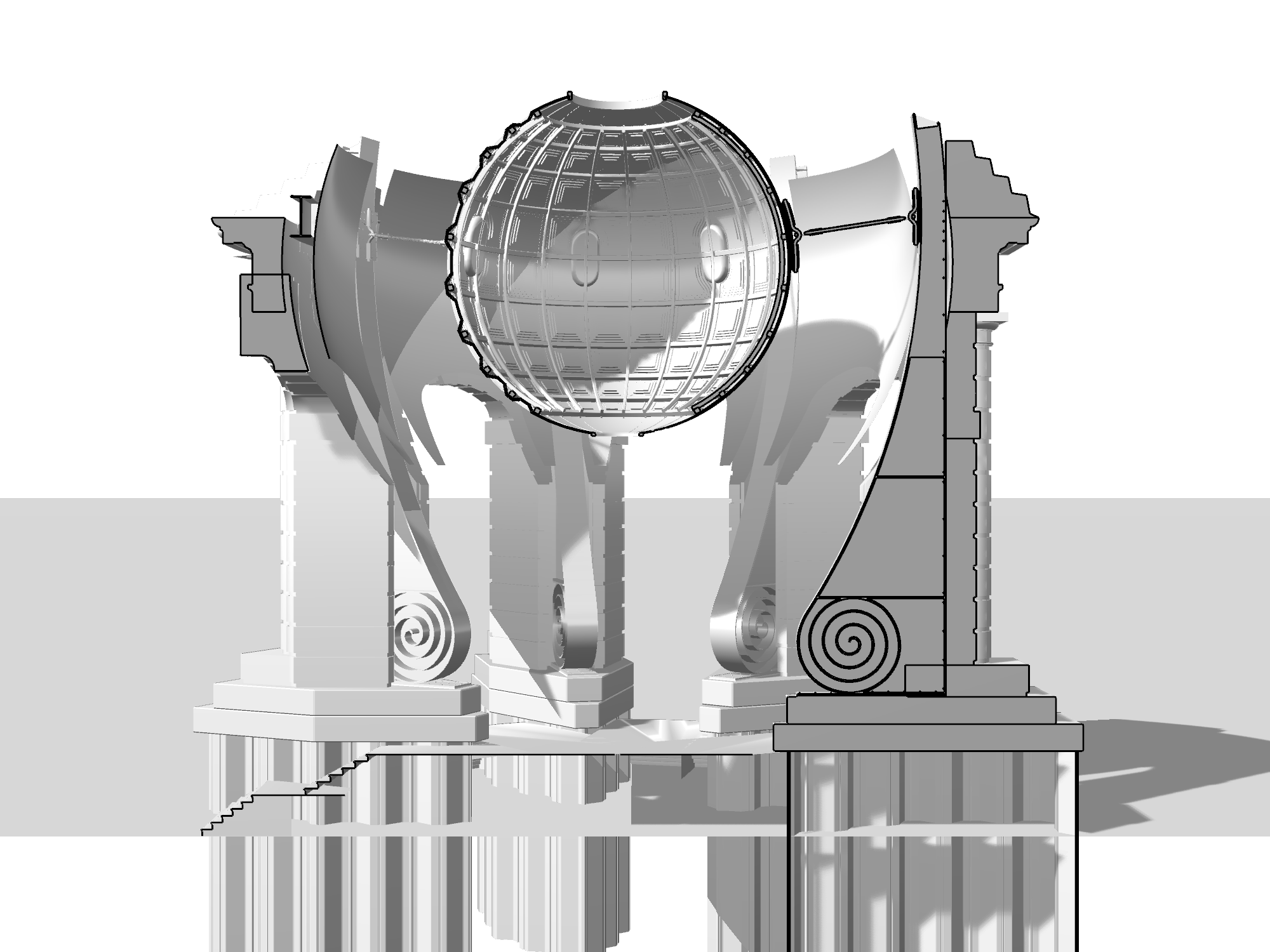

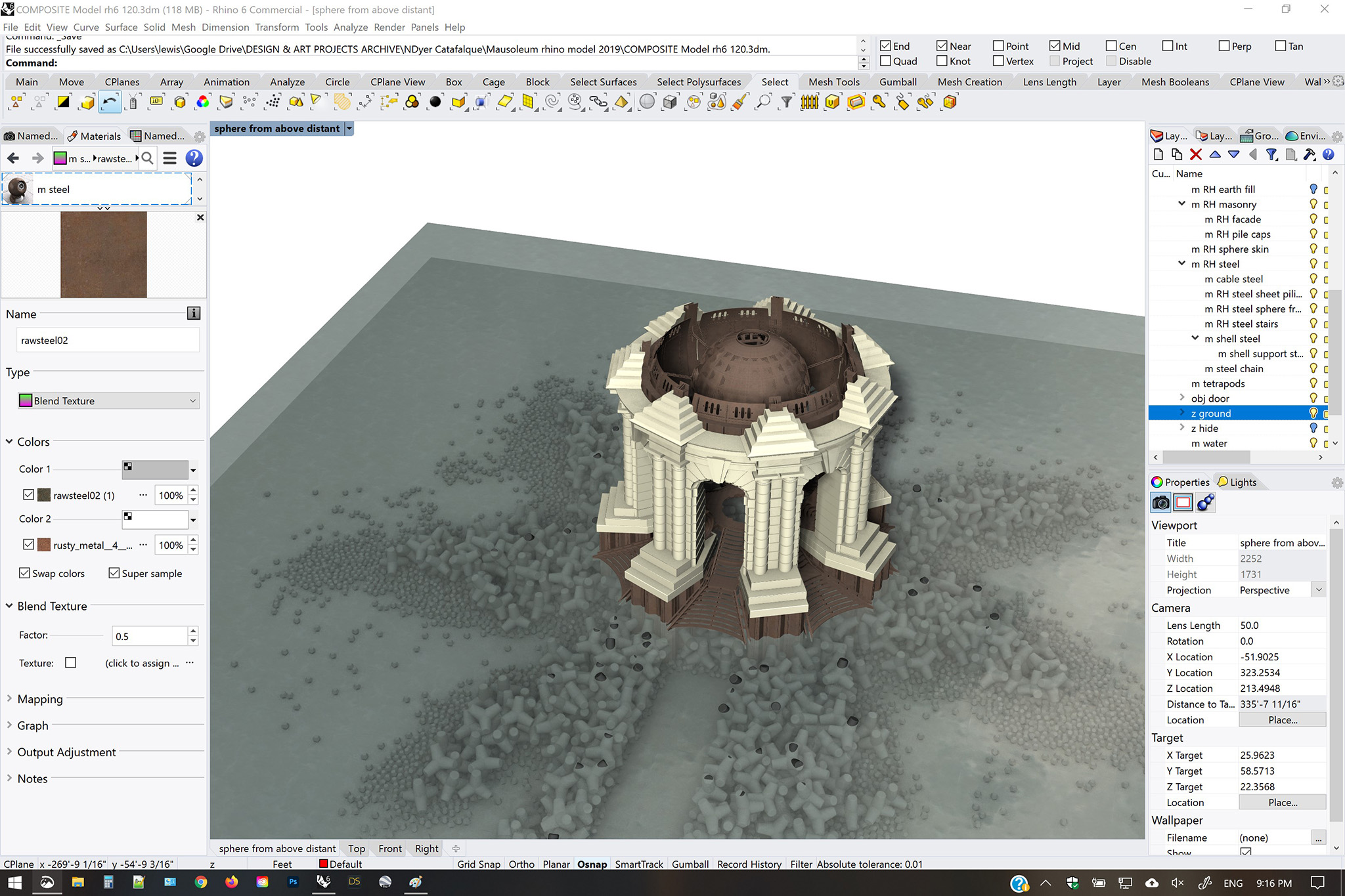

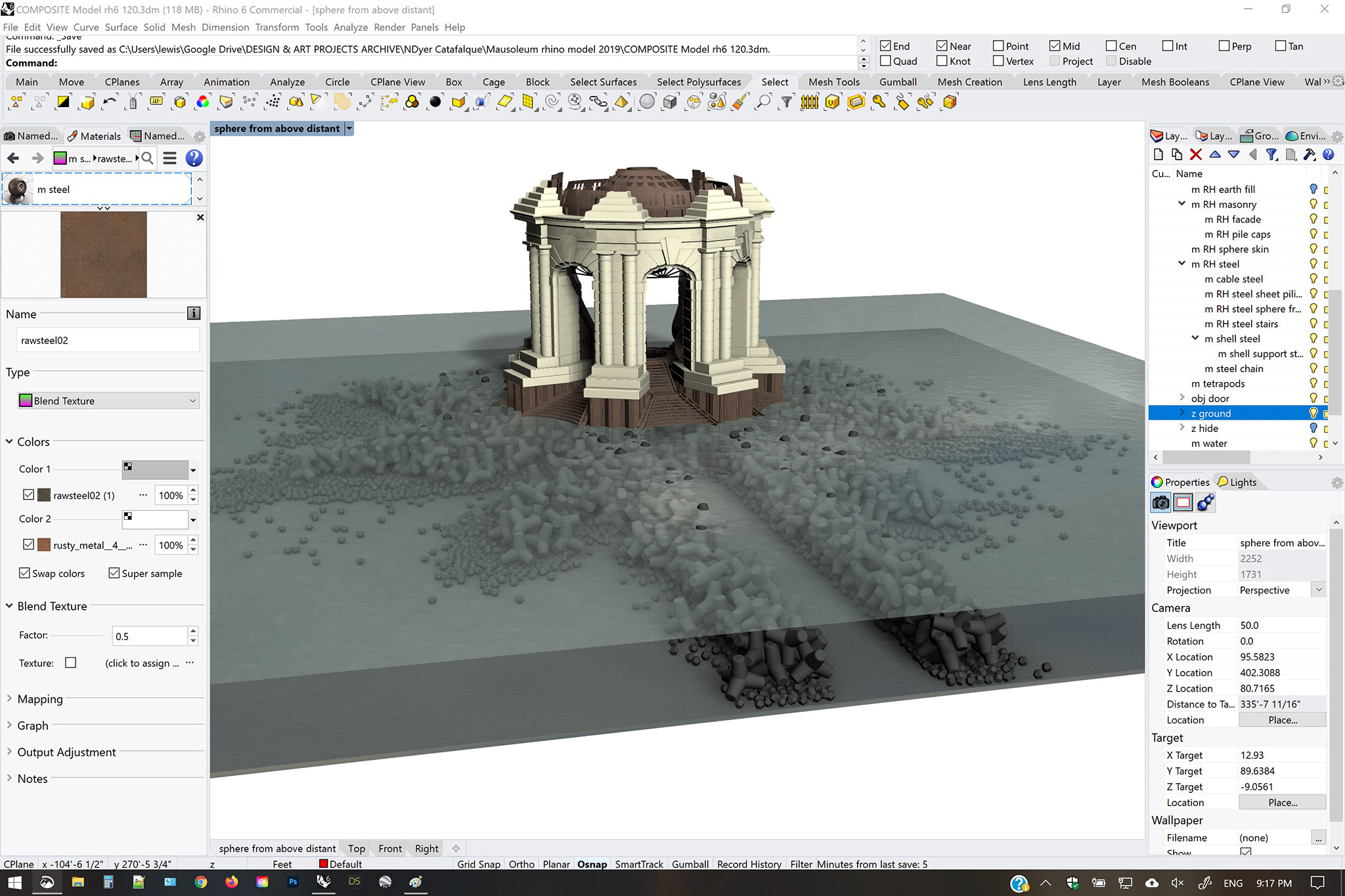

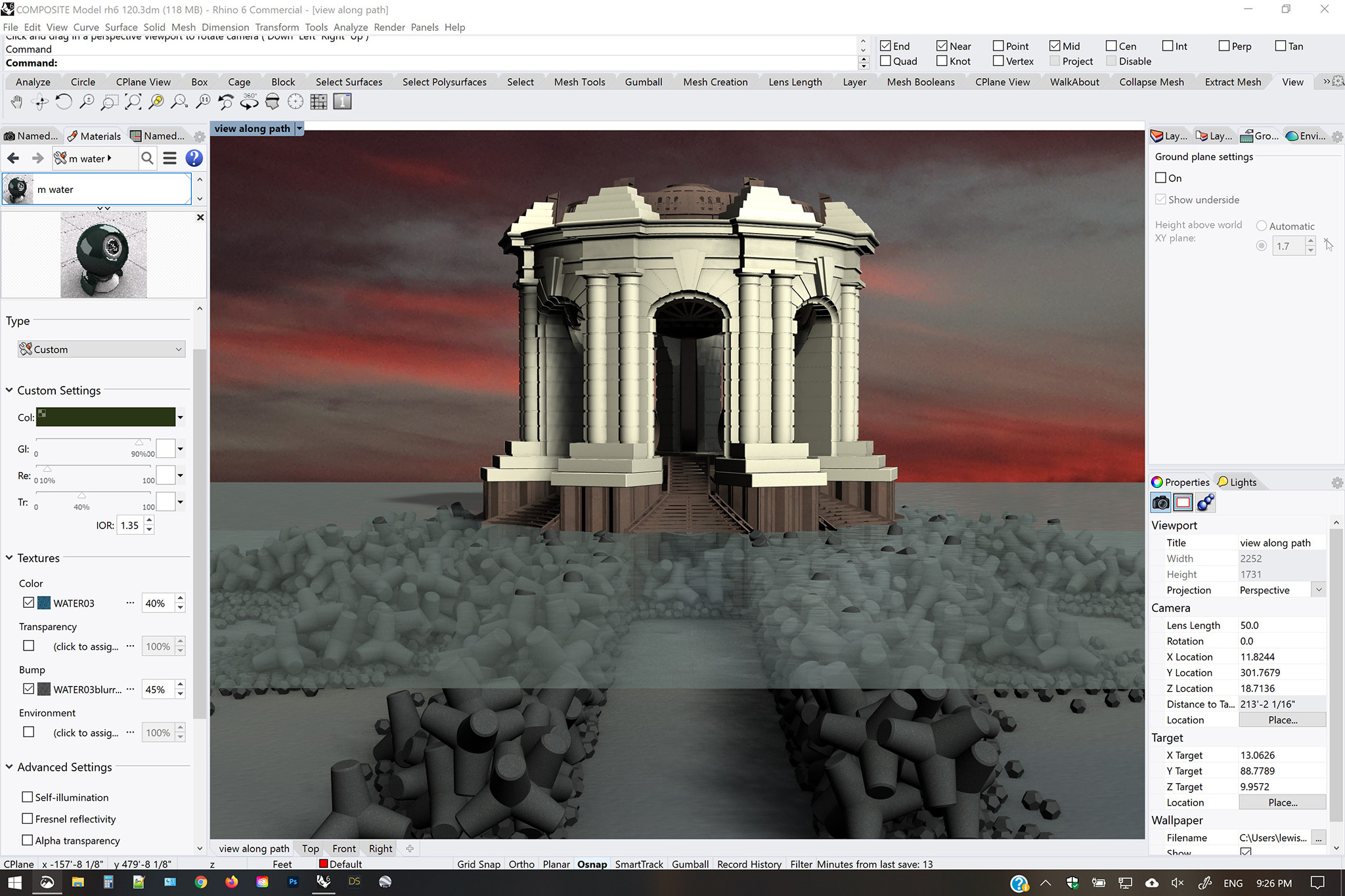

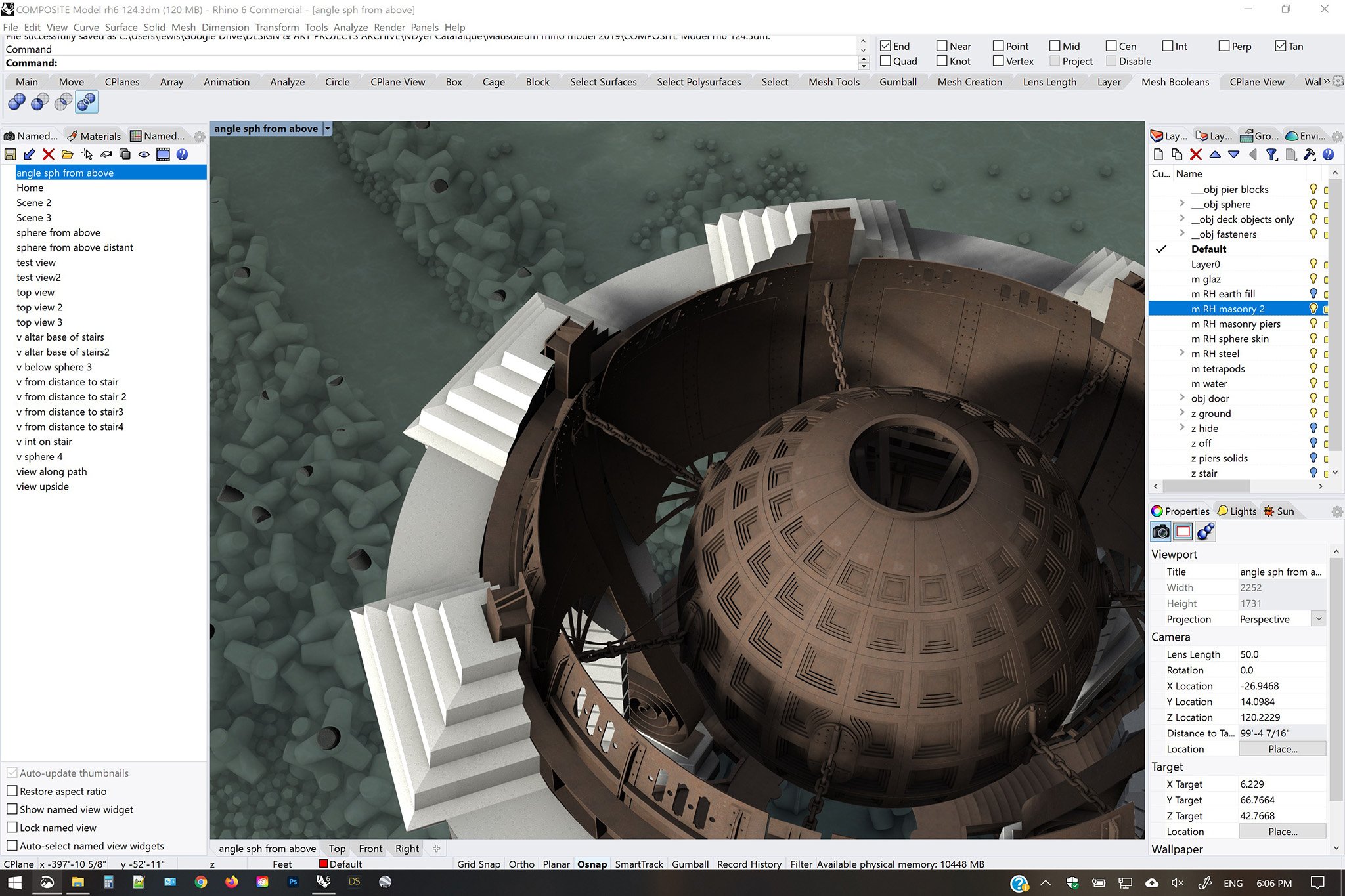

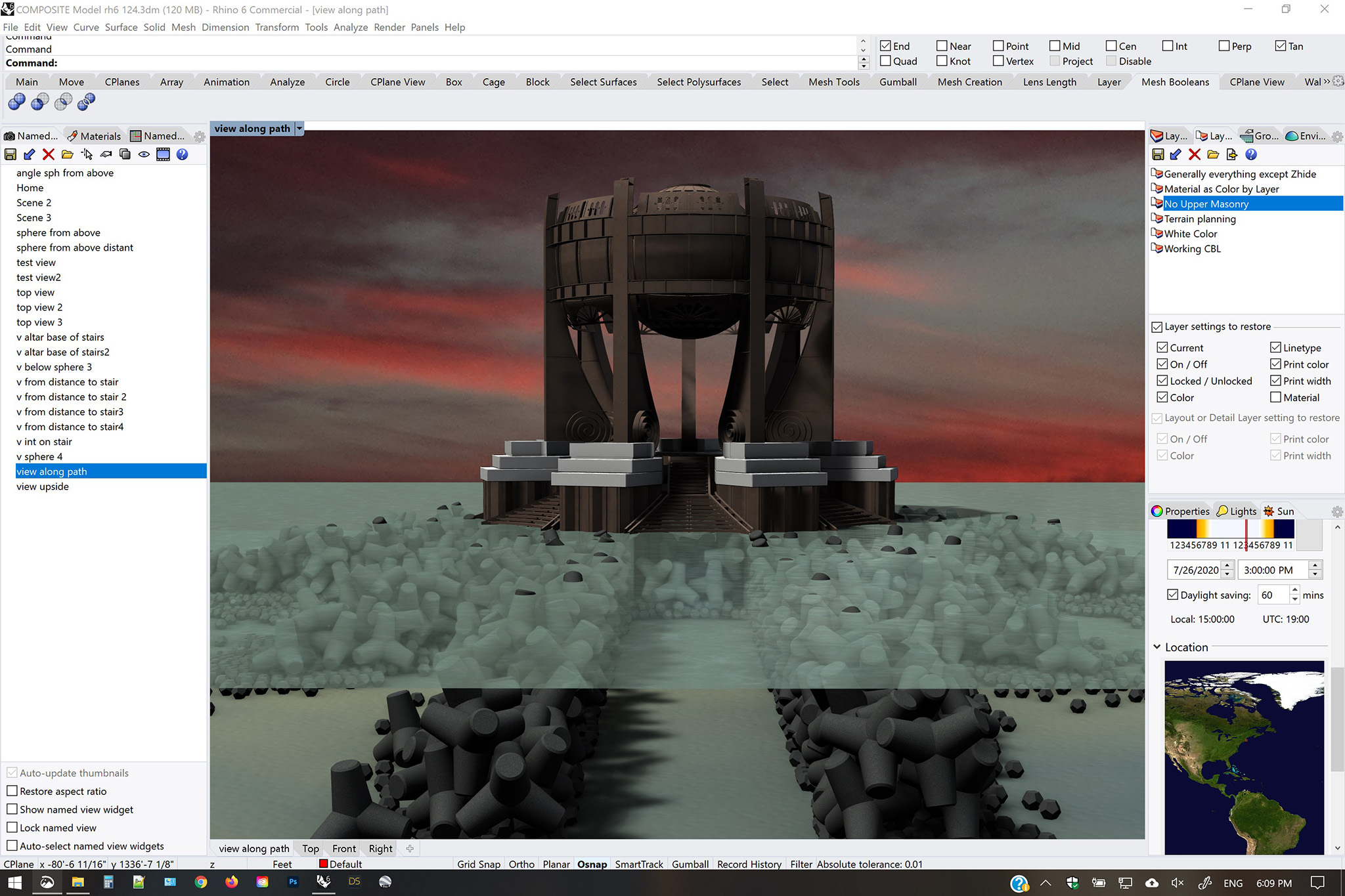

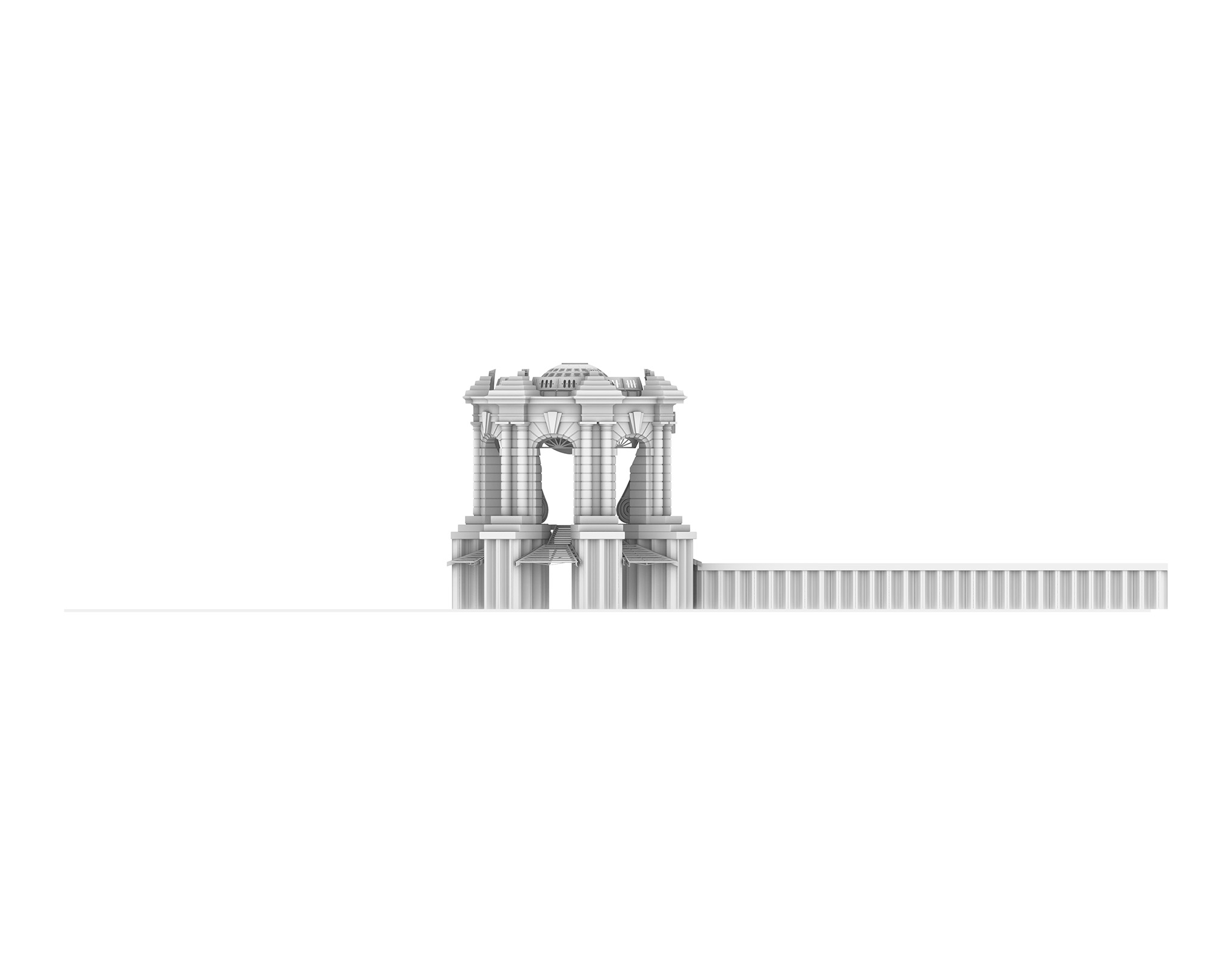

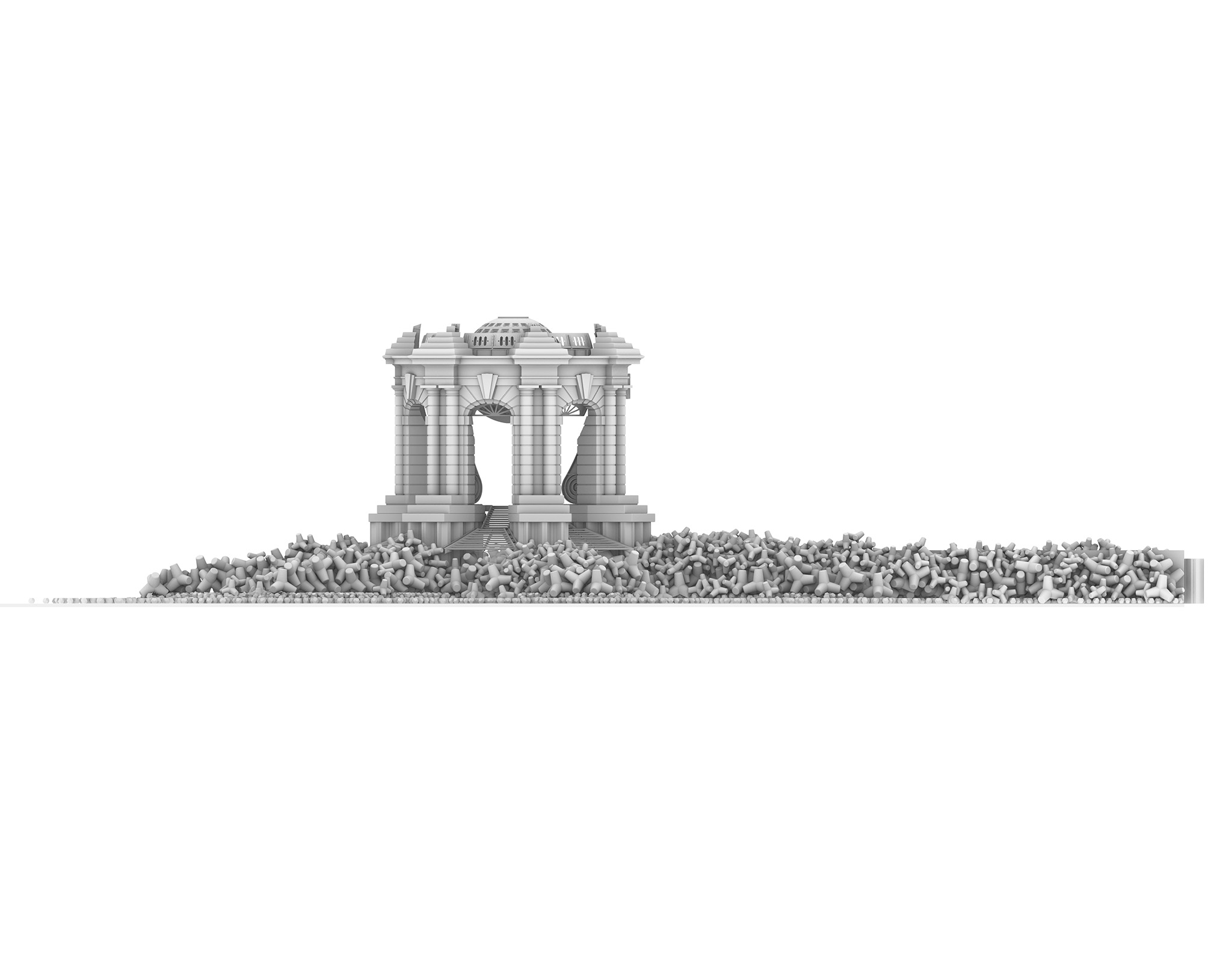

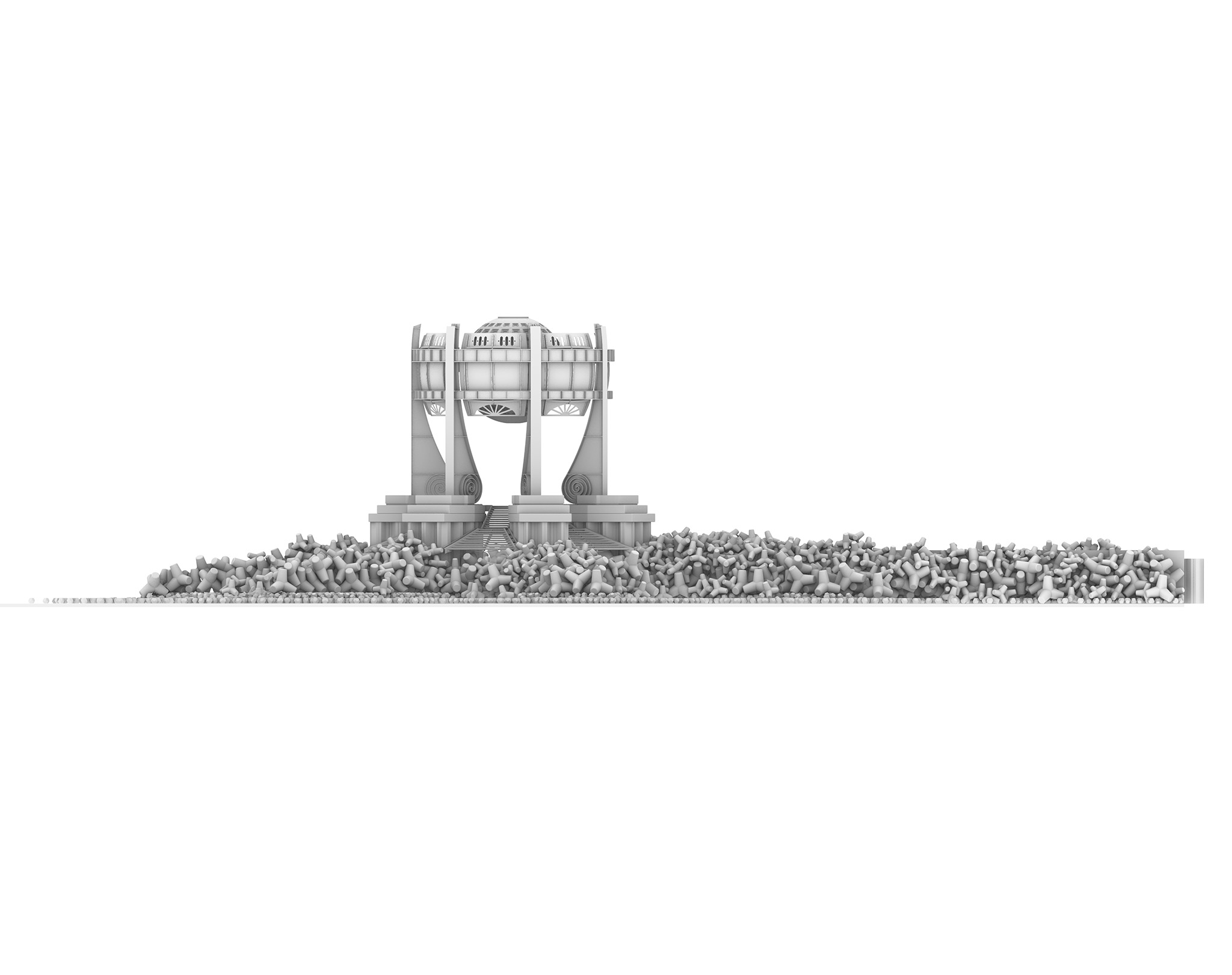

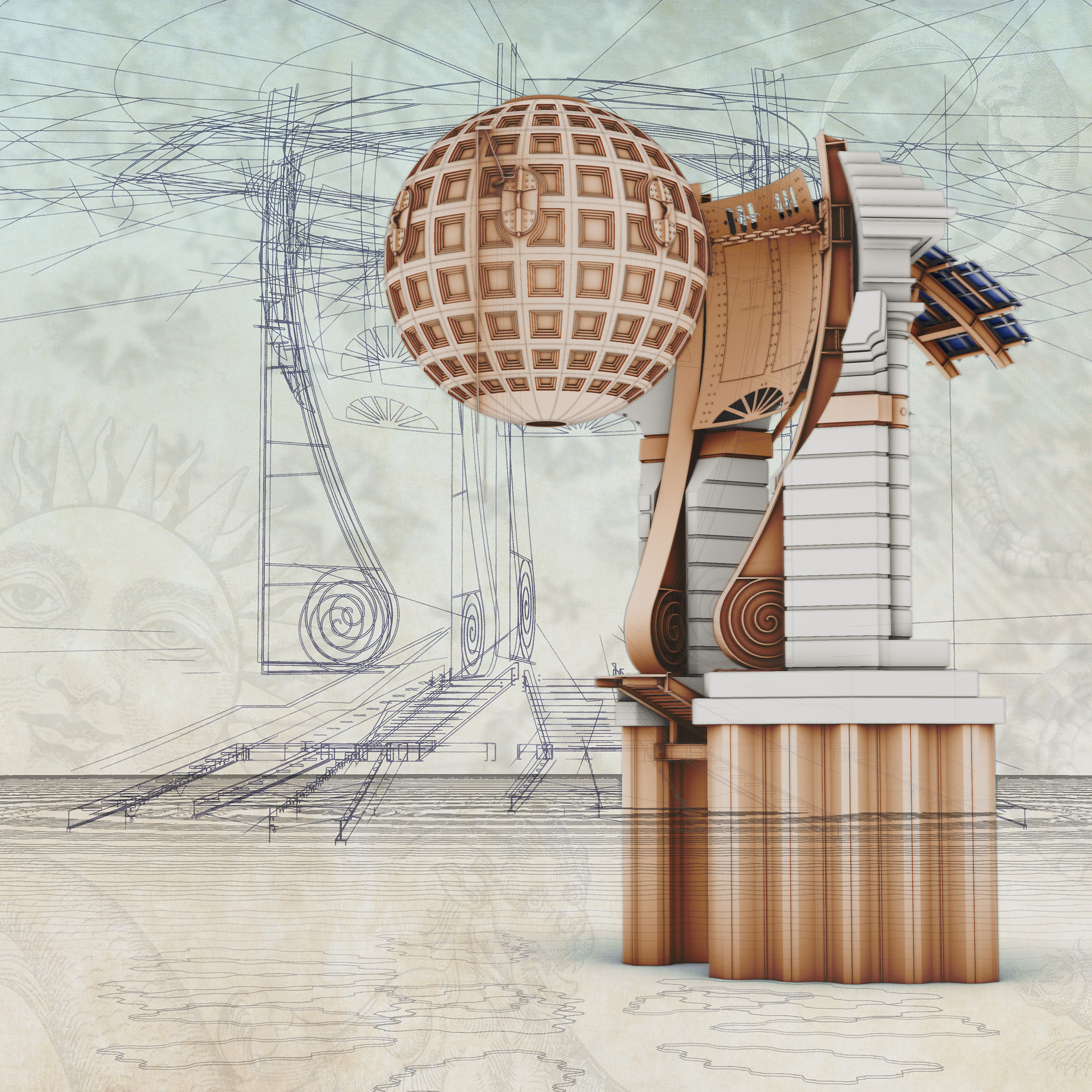

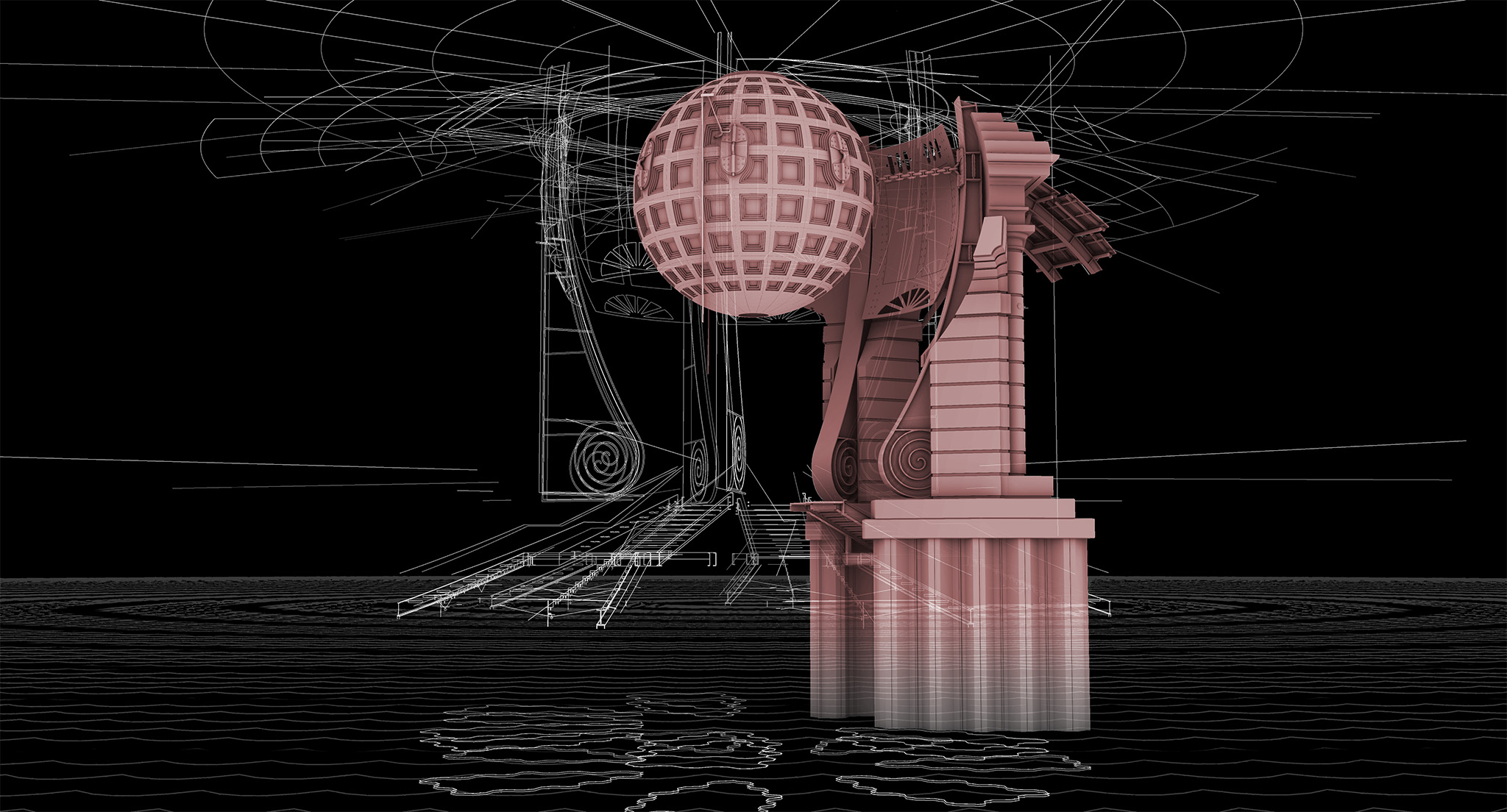

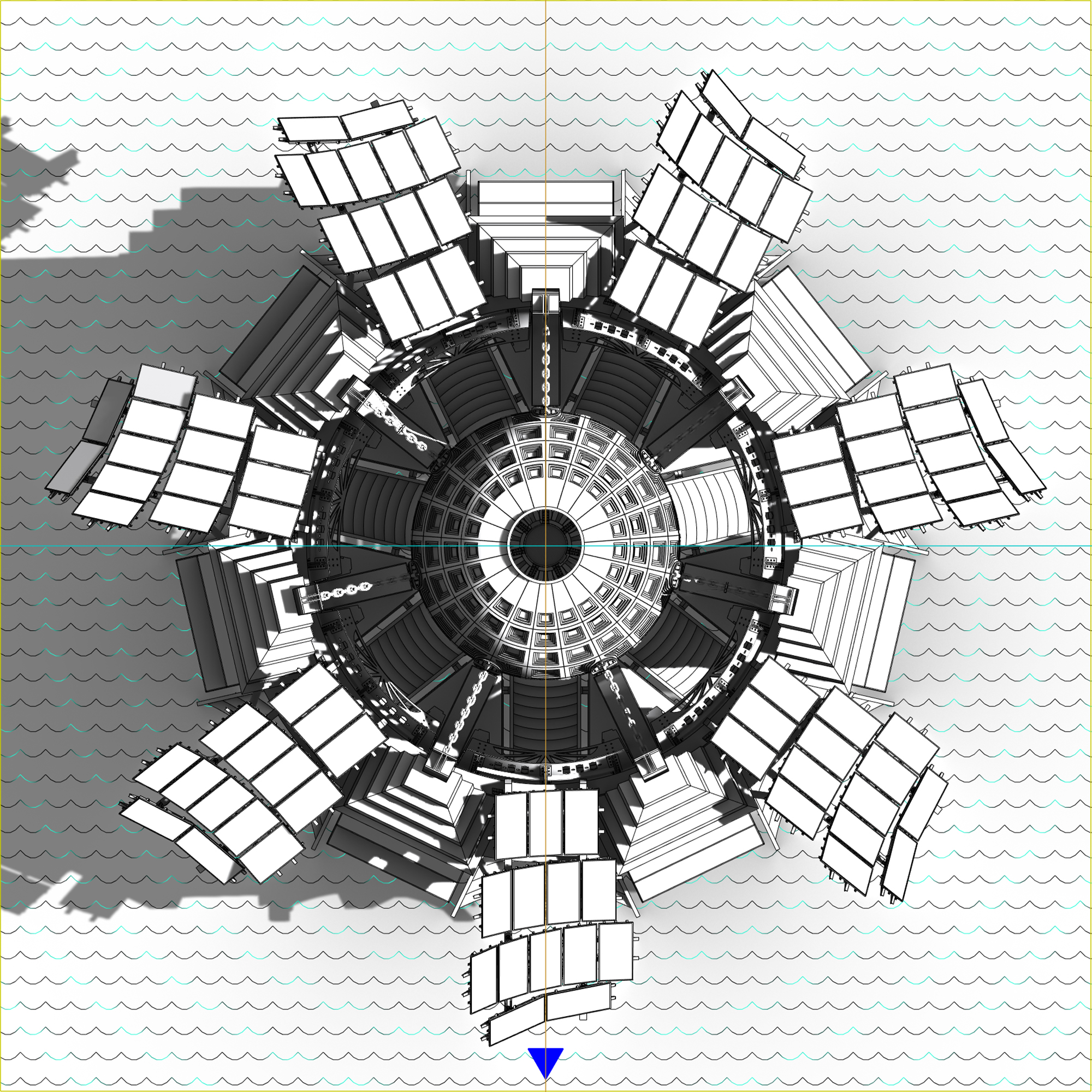

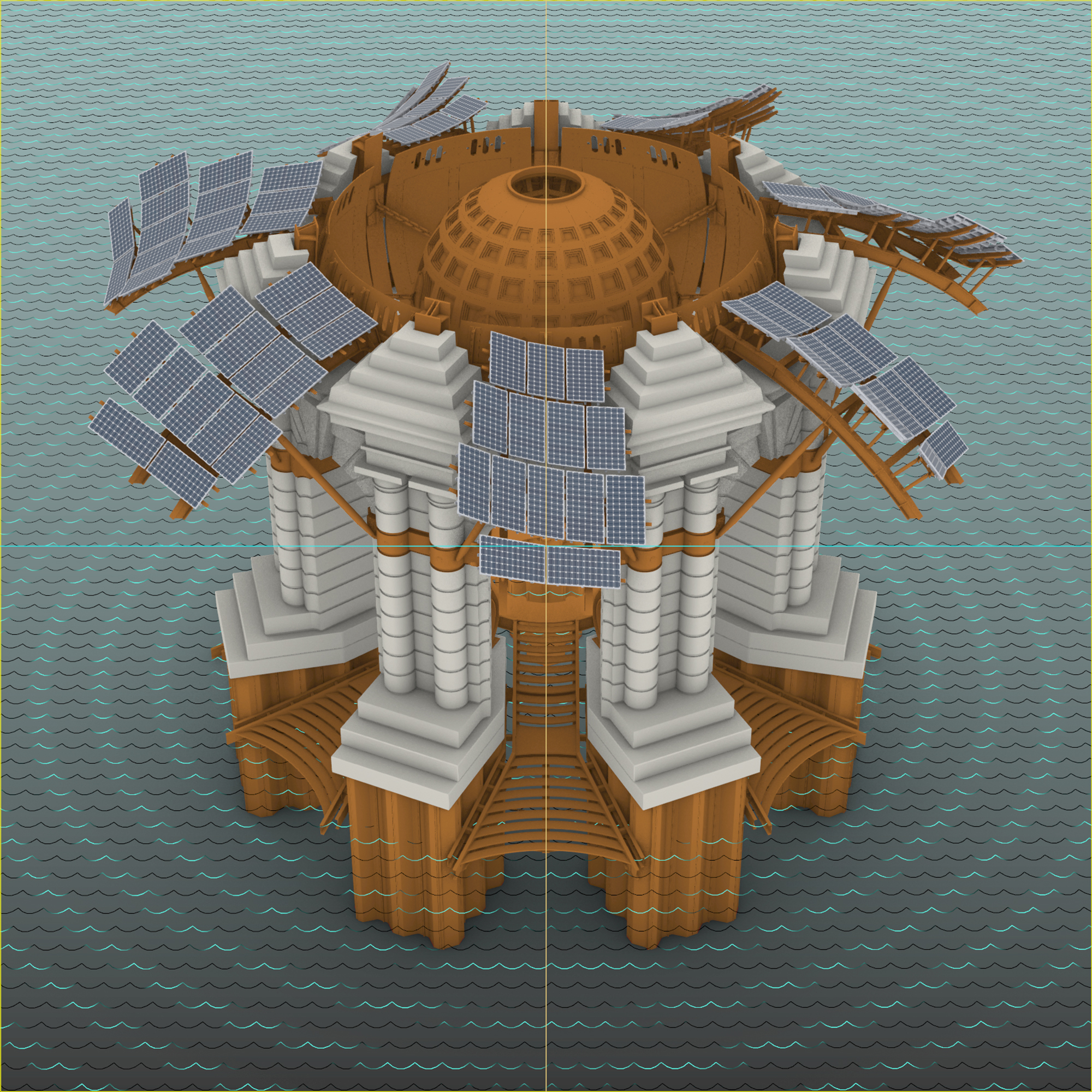

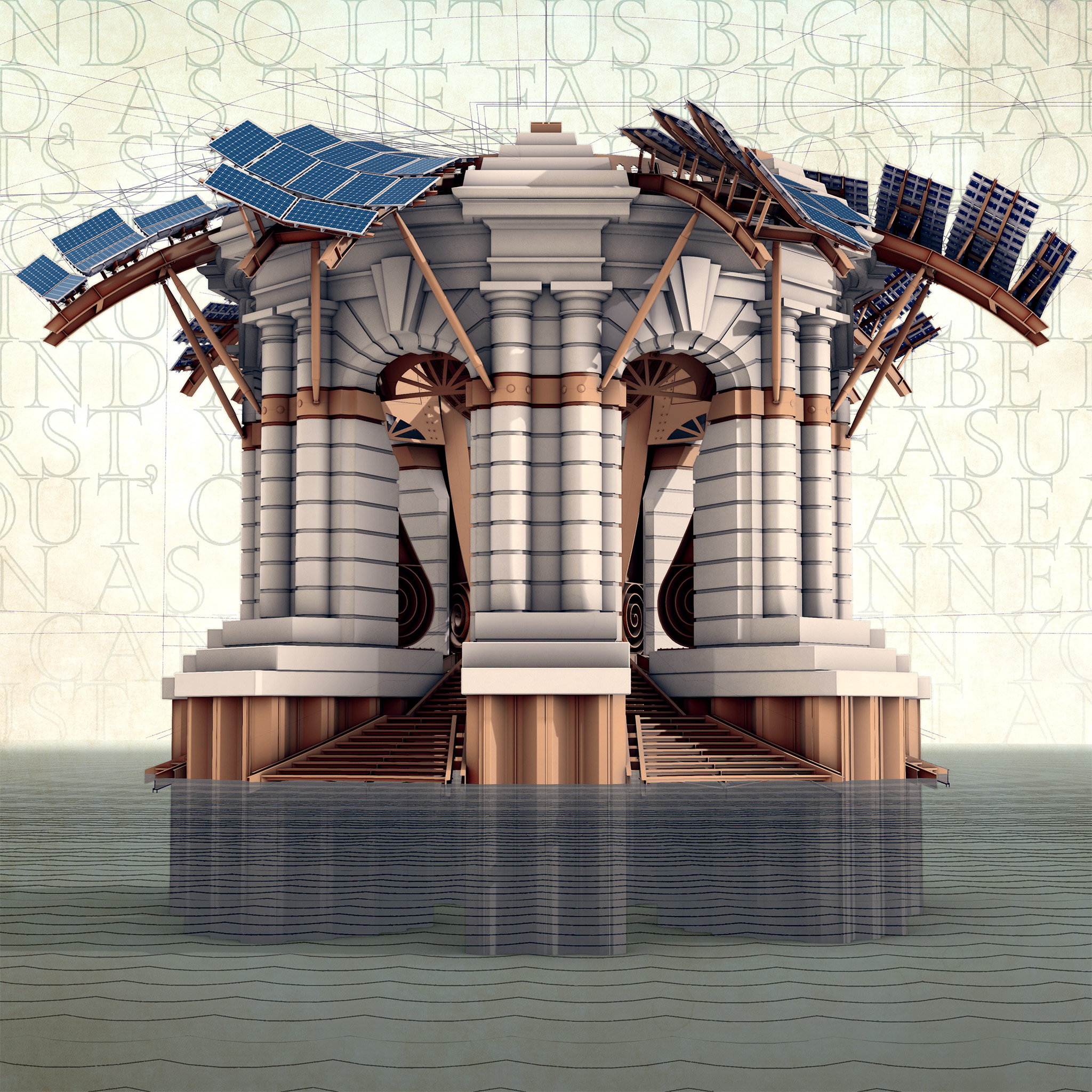

So what kind of non-church, “useless” architecture would this demoniac Nicholas Dyer design, if he somehow resumed his trade in our grim time? I worked out a strange non-classical “classicising” pavilion that mixed “trademark” Hawksmoor motifs (Tuscan columns used like some other order with arcades; unlikely rustication that obscured “the Fabricke” in a most un-antique manner, etc. — all cribbed from some project or the other executed by the actual architect in his lifetime), sitting on marine sheet piles and visibly reinforced by modern standard cross-section steel members. The hemispherical dome of the classical rotunda became a giant perforated and coffered sphere, suspended threateningly overhead using great reinforced chains. And the whole pavilion is actually seven-sided, for added non-classical-classicizing mystical-mayhem significance.

And then the whole thing bombed out and came to a crashing halt because I couldn’t develop a convincing rationale for why Dyer would design this…or worse, why I would try to imagine what a particularly-nasty fictional version of an architect from the seventeenth century would design if he somehow appeared with professional qualifications in the twenty-first.

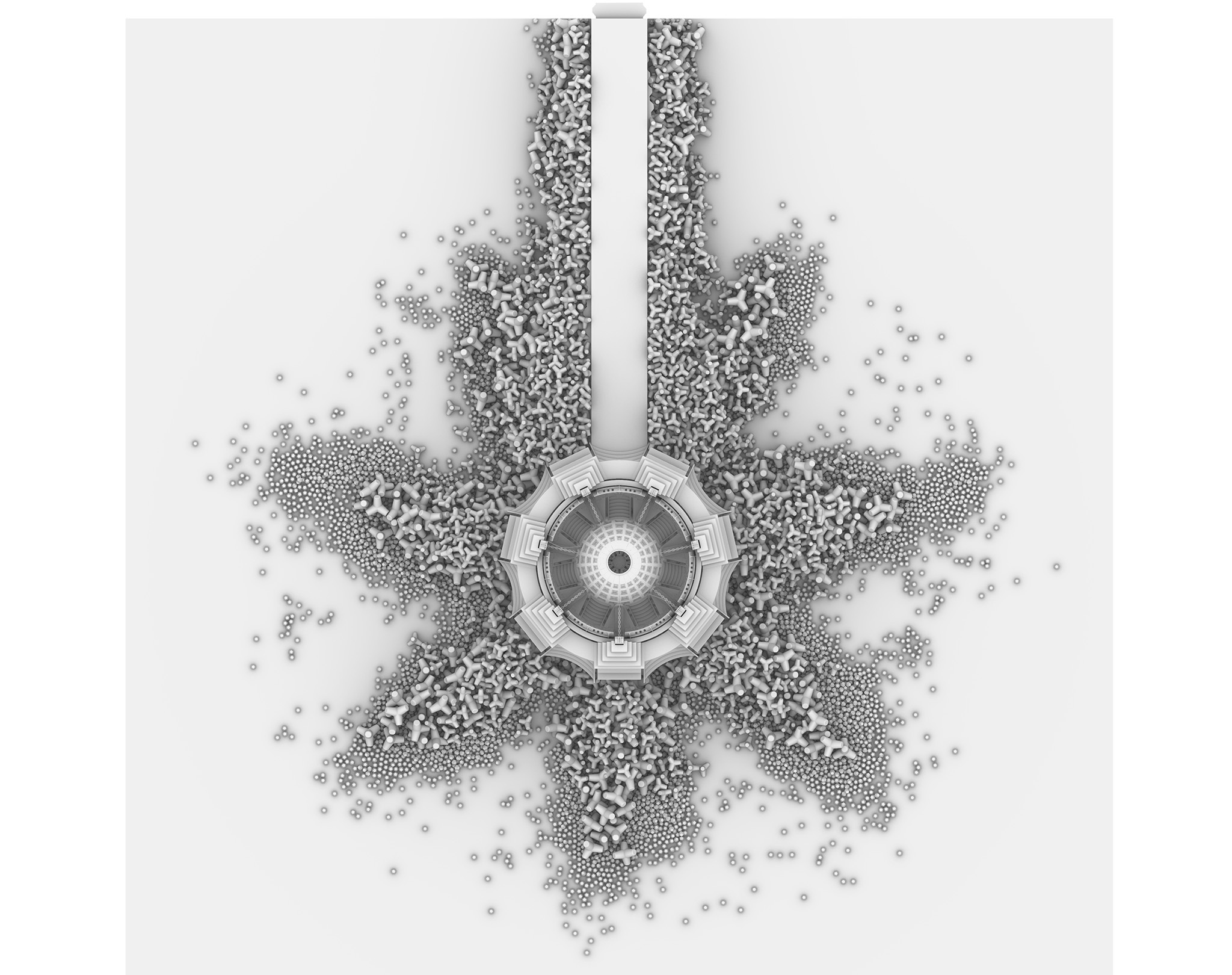

I tried again, with tetrapods in early 2020. Tetrapods make everything better, right? Wrong. What was I thinking?

Then in December 21, 2020, came the Executive Order on Promoting Beautiful Federal Civic Architecture, issued by the orange kleptocrat whose greed had ravaged the country for the previous four years and whose flailing incompetence had deprived at least a million Americans of their lives in the COVID crisis. An extended flowery exercise in faux pablum-patriotism — issued at the same moment that its originator was calling on the military to execute and torture those protesting his rule — this order of his would have required the federal government of the United States to commission and build any future facilities in a nebulously-defined Classical idiom. Without a doubt, this order would be extended eventually, if illegally, to all building in these United States.

Notable Founding Fathers agreed with these assessments and attached great importance to Federal civic architecture. They wanted America’s public buildings to inspire the American people and encourage civic virtue. President George Washington and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson consciously modeled the most important buildings in Washington, D.C., on the classical architecture of ancient Athens and Rome. They sought to use classical architecture to visually connect our contemporary Republic with the antecedents of democracy in classical antiquity, reminding citizens not only of their rights but also their responsibilities in maintaining and perpetuating its institutions.

[Make America something something again blah blah blah Rome shall have her second empire blah blah...]

I found that I quite suddenly had lost my interest in designing ersatz Graeco-Roman Classical architecture, even the oneiric or nightmarish versions of the real and fictional versions of Nicholas Hawksmoor/Dyer…at least for the moment.

In the interval, I found myself understanding that

GOING ON TOO LONG EVEN FOR EXAGG. METAFICTNL NARRATR/ DEVELOPMT OF THEORY OF CLASSICISM AS ARCHITECTRE OF DEMCRCY & FREEDM EXACT OPPOSITE ARCHIT OF OPPRESSION/ GR-ROM CLASSCM AS PREFERRED IDIOM FOR TOTALIZNG AUTHORITY/ ROME HI EMPIRE 10-25% POP ENSLAVED BEASTS OF BURDEN FURNITURE/CITE A FATAL THING HAPPENED ON THE WAY TO THE FORUM EMMA SOUTHON 2020/CF ATHENS GOLDEN AGE 13 SLAVES PER FREE MAN? DEMETRIUS PHYLARIUS LATE 4TH C CE/ MORE EXAMPLES? BRITISH IMP. FURTH RESEARCH? ROYAL AUTHORITY RESTORATION POSTFIRE LONDON RETURN TO BAROQUE PD & HAWKSMR/I SAW COTTON AND I SAW BLACK TALL WHITE MANSIONS & LITTLE SHACKS NEIL YOUNG 1970/CF? EXEC. ORDER ON BEAUT FED ARCH SEC2 COMMAND RESPECT GENERAL PUBLIC SHOOT THEM IN THE LEGS?

when in 2024 it began to seem likely that the same orange kakistocrat would regain power, and use it vindictively, I began to sense an application for my malevolent not-really-classical but classical design, à la Nicholas Dyer. Or perhaps I went mad.

Dyer, the diabolical genius version of Hawksmoor in Ackroyd’s novel, composed something more than simply baroque religious edifices; together, positioned precisely across the face of the post-Great Fire city the churches constituted a sort of psychographic mystical apparatus, aimed in theory at launching him into a sort of eternity outside of the polluted world of mortals. The book’s dénouement is open to interpretation, but it does not seem like Dyer the Demoniac Architect exactly succeeded in a quest for eternal life, assuming he was seeking that. But he may have created a very special kind of near-eternal damnation for himself, iterated over multiple incarnations, over multiple lifetimes.

What if a reincarnated Dyer, in our modern period, as that rough beast slouches toward Bethlehem, was to compose deliberately a curse in the form of architecture? Did it have to be built? Would a well-examined and critically-composed design do? Am I suggesting that I devoted nearly a year of my life to composing a speculative architectural project that amounted to a metaphysical/metafictional/simulated-mystical hex upon a once-and-future head of state?…that I relentlessly over months applied myself to a task that amounted to architectural illustration as voodoo?

Well, that would be unique, wouldn’t it? — at least outside of Ackroyd. And assuming everything I’ve written here isn’t just a prolonged exercise in metafiction.

If it wasn’t…well, I did kill off my social media accounts to prevent myself from being persecuted by the smeary orange powers that be. I was planning on keeping this project — on the assumption that someone might decide it was a serious attempt at something other than an odd marriage of architecture and literary pretentiousness — to myself, until “the coast was clear”. Or forever, if the foreseeable future really became inescapably symbolized, as in Orwell’s famous novel, by that image of a boot stamping on a human face — forever.

…except that there is some reason to believe that the target of my vague not-quite-believable malediction — is that the right word for something so visual?…except that there is some indication that my target might, in a metaphysical-metafictional-simulated-mystical fashion, have got to me first. And I have the scars and doctors’ bills to prove it.

I may be inferring too much from unfortunate coincidences.

But still: once the afore-mentioned boot has already connected with your head, what do you really have to lose?

The text stenciled around the spherical anti-dome in these renderings is the infamous curse known as the Incantation, from the unfinished epic Manfred, 1817, by George Gordon Lord Byron, who for all his louche sins died a freedom fighter. In the sectional perspective, the text of William Butler Yeats’ 1919 apocalyptic poem The Second Coming repeats endlessly across the sky and clouds. Seemingly collaged upon each rendering is one or more old paper notecards. On each card is “typed” a quotation from Executive Order on Promoting Beautiful Federal Civic Architecture; a contrasting direct quotation from the kakistocrat who issued the order is situated nearby, in a simulated “magic marker” font.

The very earliest of the finished project illustrations, the “exterior perspective with dolphins & cardboard” has a short quote from the Public Image Limited song Rise (John Lydon and Bill Laswell,1986) imposed on the clouds in the background.

The original illustrations for the project were composed with the intention of cropping them to a square, social-media-friendly format. Those that lend themselves to an un-cropped rectangular format are here presented in that configuration. Two of these renderings, the uncropped versions of the “exterior perspective at sunset” and the “section in perspective” were further modified slightly through the addition of more “notecards” to stand alone as poster-entries in an illustration competition. As I expected, they were awarded no distinction.

Readers interested in pursuing an understanding of gibbeting, a form of historic posthumous punishment also referred to as “hanging in chains”, are advised to begin with the Wikipedia article on the topic <link>.

Leave a Reply